Shaping An Aesthetic And High-Performance Façade Through Fenestration Optimization

Reimagining Public Buildings

Government organisations like the CPWD in India have a legacy of creating landmark architectural projects, which, in recent times, seldom get appreciated by the general public or the private sector.

In the past, projects in the national capital, such as Nirman Bhawan, Shastri Bhawan, Vigyan Bhawan, Parliament Annexe, to name a few, have served as examples of excellence in responsible (and fairly sustainable) design. For the time when these buildings were built, they responded to the local climatic context, respected local material choices, while developing an aesthetic that was distinctly ours. Unlike a lot of architecture these days that attempts to ape the West, these buildings dared to attempt to stand on their own feet.

The recently inaugurated CGST Bhawan in Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, exemplifies this very spirit. This too was a project that was executed under the aegis of the CPWD. Designed by Delhi-based architects Studio Next, assisted by Psi Energy Pvt Ltd as sustainability experts and constructed under EPC mode by the youthful, second-generation leadership of Kashyapi Infrastructure Private Limited, the building will serve as the regional headquarters for the Central GST Commissionerate for the state of Uttar Pradesh.

Project Description & Planning

CGST Bhawan is a 30,000 sqm Multistorey office building for the GST (Goods and Services Tax) and its affiliated departments located in Ghaziabad, UP. The building is G+7 of office space (17000 sqm) with an additional double basement for parking.

The U-shape plan of the building provides ample daylight into the office spaces as well as creates a self-shaded courtyard for staff activities. The central courtyard with steps leading to the pre-function space of the Multipurpose Hall allows for a flexible outdoor-indoor space. Acting as an open-air theatre for various teams and cultural events, it creates a welcoming environment that fosters community interaction and enhances overall well-being.

Each of the floors houses the respective departments of GST, with department heads at the ends of each floor. All public-facing functions are located on the ground floor, with some extending to the first floor for accessibility and controlled movement, such as the reception, waiting area, conference rooms, Cafeteria, and Multipurpose Hall. The upper floors house the various GST divisions and departments, organised based on their hierarchical and operational needs. This vertical zoning reinforces clarity, operational efficiency, and institutional order.

Architectural Language And Identity

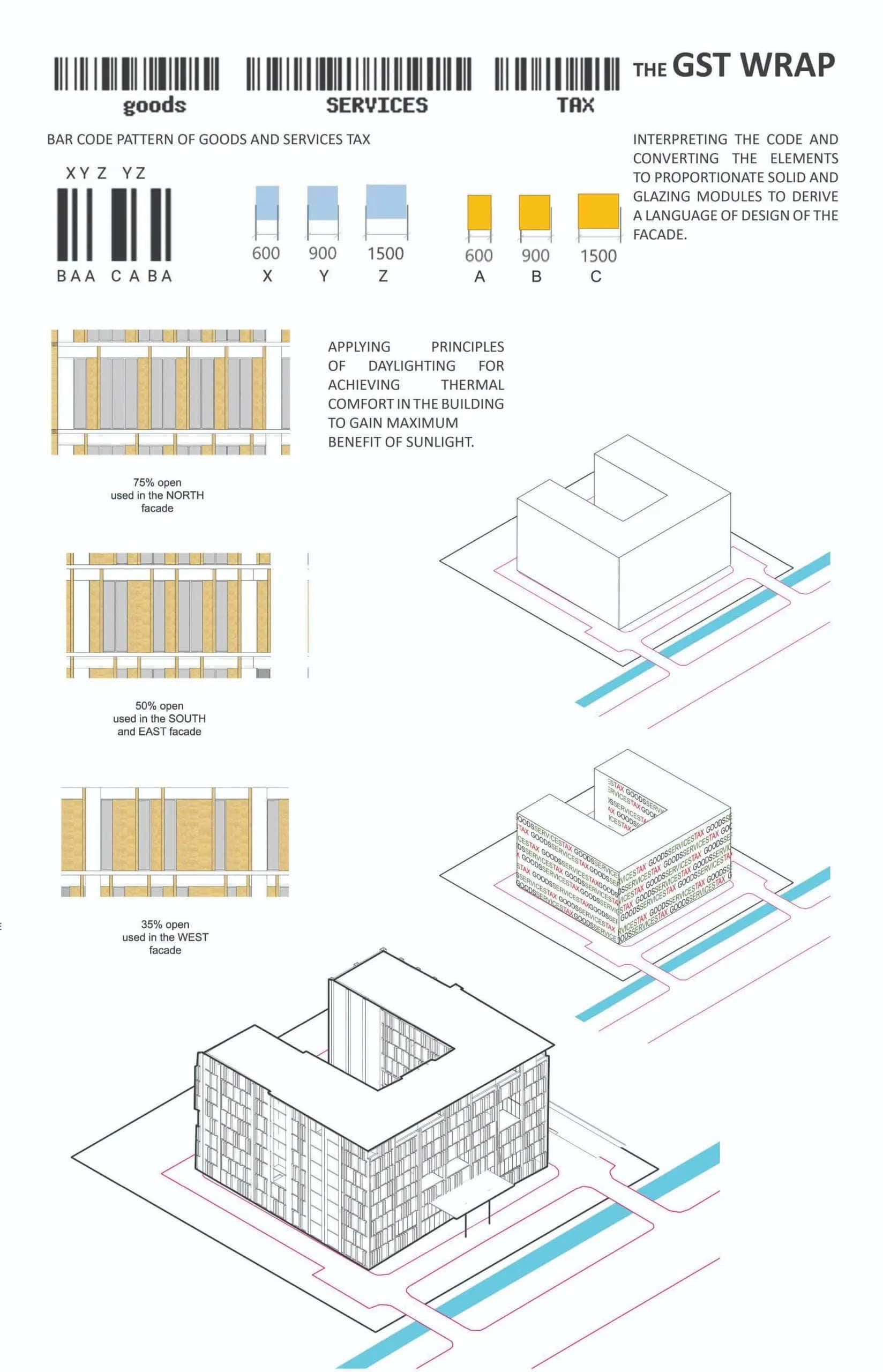

The stone-clad façade of the building is based on the barcode language of “Goods & Services tax” wrapped around the building. The barcode has been converted into proportionate solid and glazing modules to create a language for the whole façade. The design reflects the symbolic digital transformation of the country’s financial system. Overall, this provides a visual rhythm and identity for the building.

The façade further incorporates locally available stone — Dholpur stone and red sandstone — celebrating regional craft and providing a tactile, grounded materiality that resonates with institutional permanence and civic dignity.

Design Matters

Beneath this striking geometry, however, lies another story: one of rigorous environmental analysis, data-driven iteration, and integrated design collaboration. From the earliest concept stage, the architectural design team (StudioNext) and the sustainability consultants (Psi Energy Pvt. Ltd.) worked in close synergy to shape a façade that was not only aesthetically compelling but also visually and thermally efficient.

| Building component | Ahmadabad (223.037 MWh) |

Mumbai (201.892 MWh) |

Nagpur (198.756 MWh) |

Pune (137.764 MWh) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooling load (MWh) | Percentage of annual cooling load | Cooling load (MWh) | Percentage of annual cooling load | Cooling load (MWh) | Percentage of annual cooling load | Cooling load (MWh) | Percentage of annual cooling load | |

| Walls | 81.141 | 36.4 | 66.532 | 33.0 | 71.151 | 35.8 | 36.487 | 26.5 |

| Roof | 18.996 | 8.5 | 15.148 | 7.5 | 17.845 | 9.0 | 12.288 | 8.9 |

| Ground | 4.957 | 2.2 | 4.557 | 2.3 | 3.000 | 1.5 | -0.129 | -0.1 |

| Window (Conduction + Direct Solar) |

117.941 (28.563 + 89.378) |

52.9 (12.8 + 40.1) |

115.654 (17.405 + 98.249) |

57.3 (8.6 + 48.7) |

106.761 (19.608 + 87.153) |

53.7 (9.9 + 43.8) |

89.119 (6.180 + 82.939) |

64.7 (4.5 + 60.2) |

Every shading device, recess, and glazing proportion was tested, simulated, and refined to ensure the final design balanced form, function, comfort and performance – without compromising architectural intent.

This article simplifies and distils that process for readers in the facade and fenestration industry—illustrating how early collaboration and simulation-driven design can create architecture that both performs and inspires.

Climate Is The Context – Where Does The Heat Come From?

Before solving the design challenge, we needed to define it. A seminal publication by Prof. J. K. Nayak and J. A. Prajapati of IIT Mumbai, Handbook on Energy-Conscious Buildings, reveals a simple yet crucial insight: windows are the single largest contributors to heat gain in the building envelope. Which is why national codes like the ECSBC 2024 require compliance with a 40% window-to-wall ratio in their prescriptive approach.

As shown in the Table above, across major Indian cities, fenestration accounts for 52.9–64.7% of the total annual cooling load—far exceeding that of walls and roofs. Walls contribute only 26.5–36.4 %, and roofs less than 10 %. This pattern, consistent across dry-hot (Ahmedabad), warm-humid (Mumbai), composite (Nagpur), and temperate (Pune) climates, highlights how solar radiation through glazing significantly influences both occupant discomfort and energy demand.

Now, you may notice that these locations fall under latitudes far south of the national capital territory of Delhi, where the peak summer temperatures can reach a high of 50 degrees C, and winter can drop to a low of 5 degrees Celsius.

The CGST Bhawan, located in Ghaziabad, faced an even sharper challenge. The location of the plot/site restricted the design team from playing with the orientation of the building. The main façade of the building, which faces the main road (Rani Jhansi Marg, Sector 11, Ghaziabad), would likely face high solar radiation intensity during summers, tending to amplify conductive and radiant heat gains and glare conditions. This west-facing façade, as per the National Building Code 2016, is an orientation with the second-highest incident solar radiation in summer.

However, with ample setbacks, the team carefully designed each orientation for maximum performance and minimum energy consumption.

The Critical West Façade

The west-facing façade, as previously noted, happened to be the main road-facing façade—the symbolic “barcode” would become the face of the government institution. This surface represented both architectural identity and thermal vulnerability: the building’s most celebrated elevation also received substantial solar exposure throughout the day.

Recognising this at the concept design stage was critical. Had the issue been discovered later—during construction or post-occupancy—it would have been costly and complex to retrofit. Solutions at that point would likely have relied on expensive glazing or shading solutions, or worse still, HVAC-based compensation, undermining both energy efficiency and architectural coherence.

By proactively simulating the west façade, the design and simulation teams ensured that the building’s most visible surface also became its most efficient, preventing long-term inefficiencies and reinforcing the government’s public image as modern, data-driven, and environmentally responsible.

The Iterative Co-Design Process-Design And Simulation In Sync

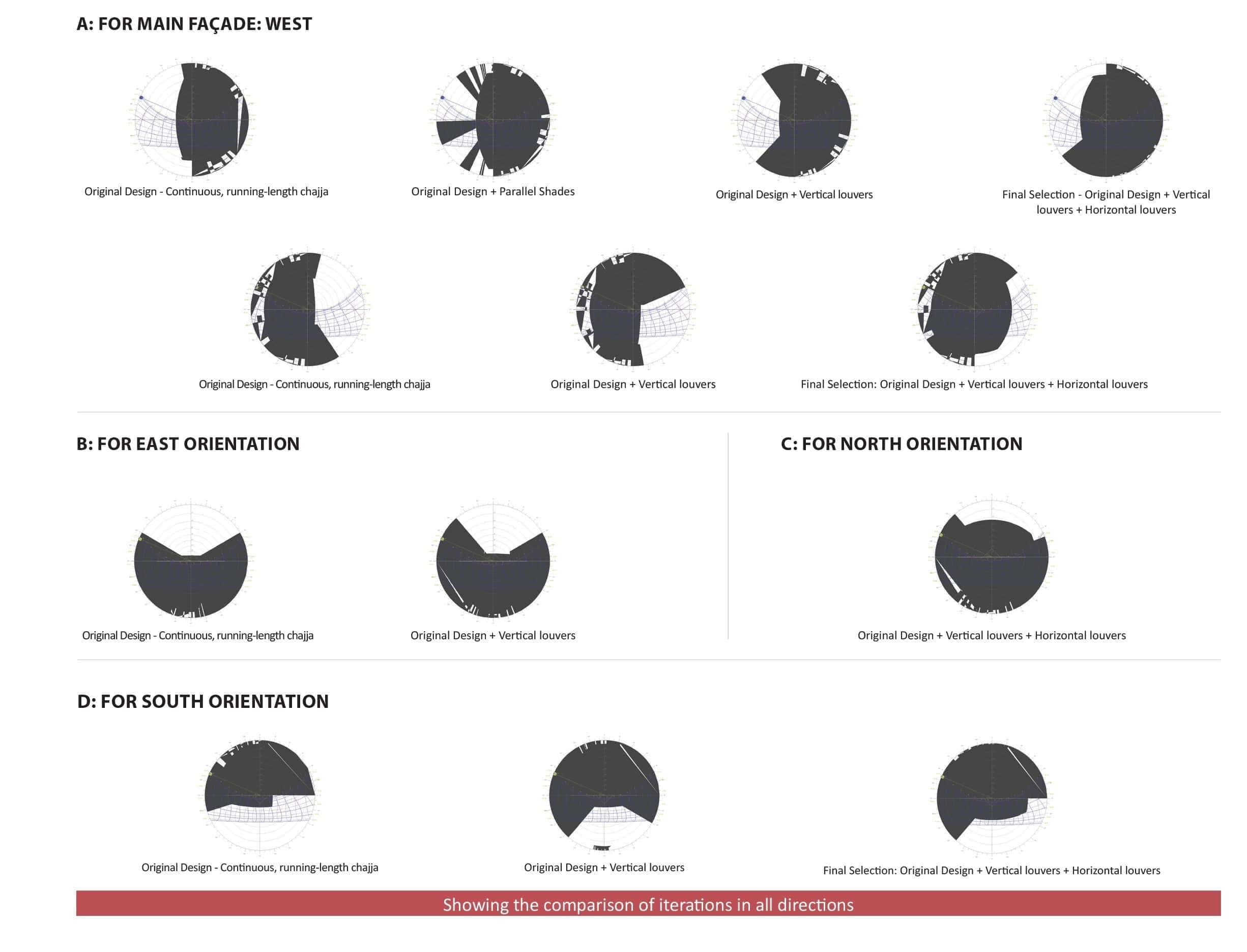

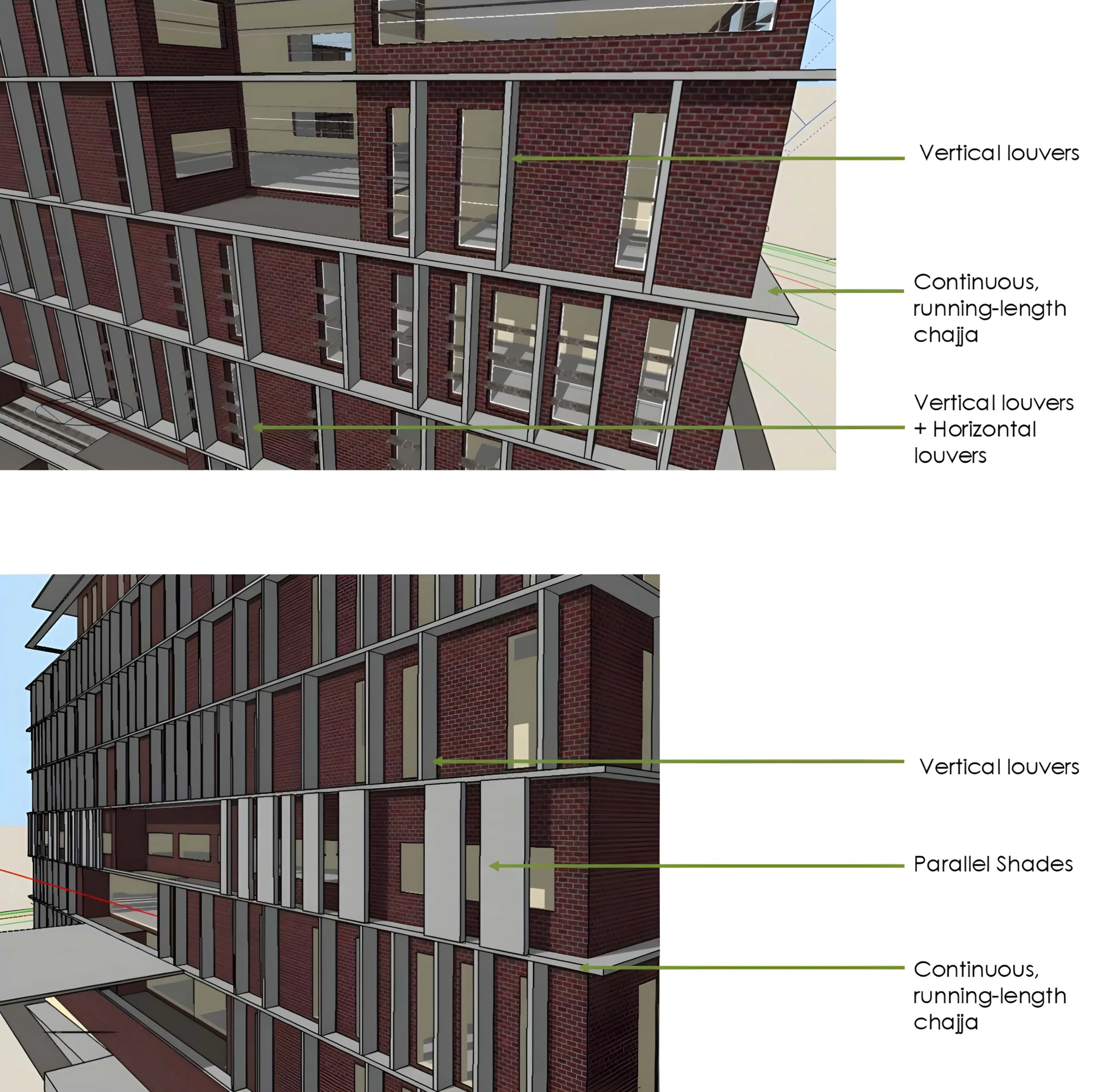

Understanding the Sun Path Diagram. Using early-stage building-performance software, a series of parametric models was developed to simulate the impact of various shading strategies that enhanced the design intent and did not disrupt it. The primary iterations included (as shown in Figure 1):

- Original Design – Continuous, running-length chajja.

- Original Design + Vertical louvers

- Original Design + Parallel Shades

- Original Design + Vertical louvers + Horizontal louvers

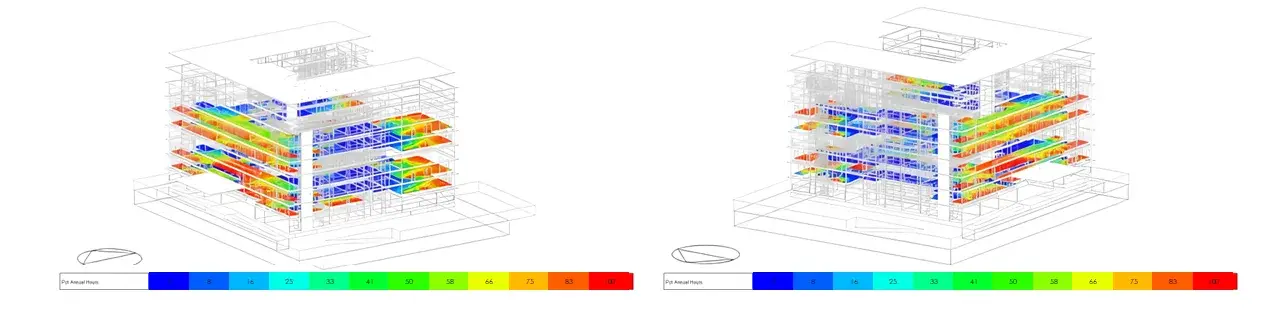

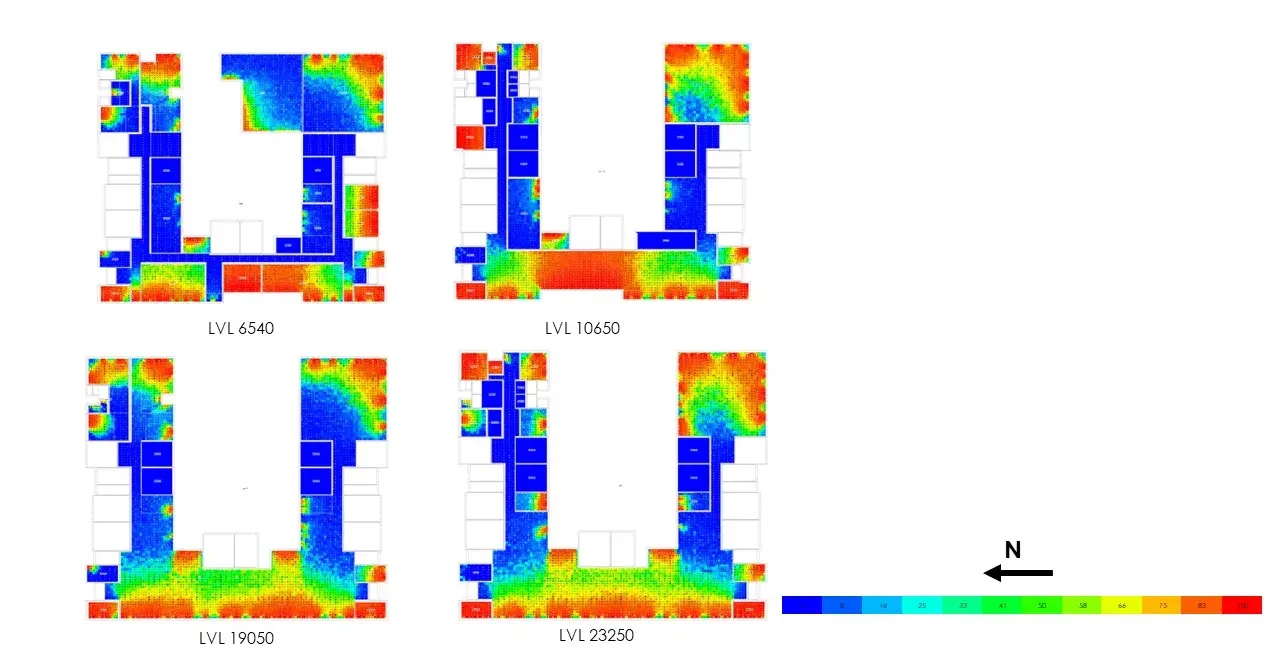

Each variation was analysed using sun-path diagrams combined with solar-radiation data. The architectural and simulation teams jointly reviewed outputs-heat-gain charts, fabric and ventilation graphs, and Useful Daylight Illuminance (UDI) simulations for each floor—before finalising the most balanced configuration.

This feedback loop transformed the façade from a static visual composition into a data-responsive envelope. The final design achieved the optimal trade-off between shading efficiency, daylight penetration, and aesthetic integrity, substantially reducing solar ingress while maintaining the barcode’s distinctive visual rhythm.

Quantifying The Impact – The Science Of Shading

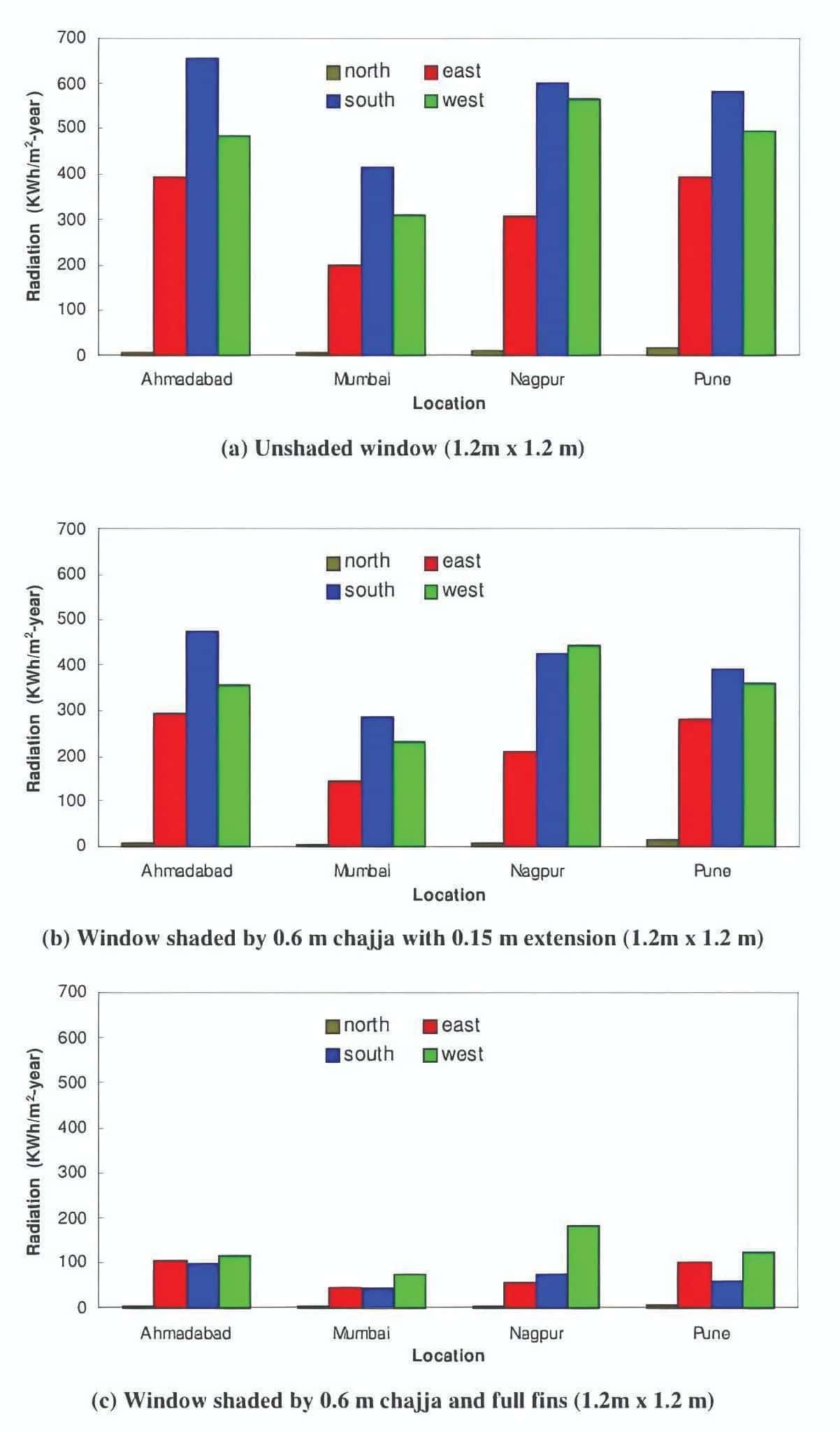

Quantifying shading performance was essential to validate design intuition. The graph below, also from the Handbook on ‘Energy conscious buildings’ by J.K. Nayak & J.A. Prajapati, summarises the results of yearly beam-radiation simulations for windows facing north, east, south, and west under different shading conditions.

One can clearly see that an unshaded window with regular glass lets in 4 to 6 times the incident solar radiation.

- Unshaded windows (1.2 m × 1.2 m) received up to 650 kWh/m2-year of solar radiation on west façades in Nagpur and Pune climates, and slightly lower but still significant levels in Ahmedabad and Mumbai.

- Introducing a 0.6 m chajja with a 0.15 m extension reduced the radiation by nearly 45–50 % on average.

- Adding vertical fins in combination with the chajja cuts it further by 70–80 %, particularly for east and west orientations where the sun is lower in the sky.

These findings echoed timeless principles of traditional Indian architecture: the right shading at the right angle outperforms expensive glazing in most Indian climates.

For Ghaziabad, this meant deep horizontal overhangs to block high summer sun and vertical fins to intercept low-angle rays. The benefits were twofold:

- Visual: Glare was minimised, and daylight diffusion improved, enhancing comfort and productivity for occupants.

- Thermal: Solar heat gain was dramatically reduced, easing the building’s thermal stress and, resultantly, its cooling load.

The Barcode Façade – Where Symbolism Meets Performance

The architectural expression of the GST Bhavan is bold yet disciplined. Alternating opaque and glazed bands reinterpret the barcode as an architectural language, translating economic identity into built form. Behind this metaphor, every proportion and recess was fine-tuned for environmental performance.

Louvers, chajjas, and glazing widths were precisely aligned to the rhythm. The main façade—facing the arterial road—combined vertical louvers and horizontal overhangs, their spacing derived from the barcode proportions. This system unified aesthetic order with functional performance, ensuring both visual harmony and solar control. Additionally, the exterior wall is a sandwich-insulated wall to reduce thermal heat gain. Importantly, sustainability was not treated as an aesthetic compromise, which is how most designers perceive sustainability inputs today.

Sustainability is not about changing the design in the name of passive design-it’s about making the design perform better while retaining the design intent. The façade thus evolved into a seamless blend of architectural expression and environmental intelligence-an identity that performs as beautifully as it looks.

“From Its Barcode-Inspired Façade To The Sunlit Stepped Courtyard And The Layered Programmatic Hierarchy, The Architecture Reflects The Ethos Of India’s GST System: Organised, Inclusive, And Forward-Thinking. The Project Sets A New Benchmark For Institutional Buildings In The Public Realm.” |

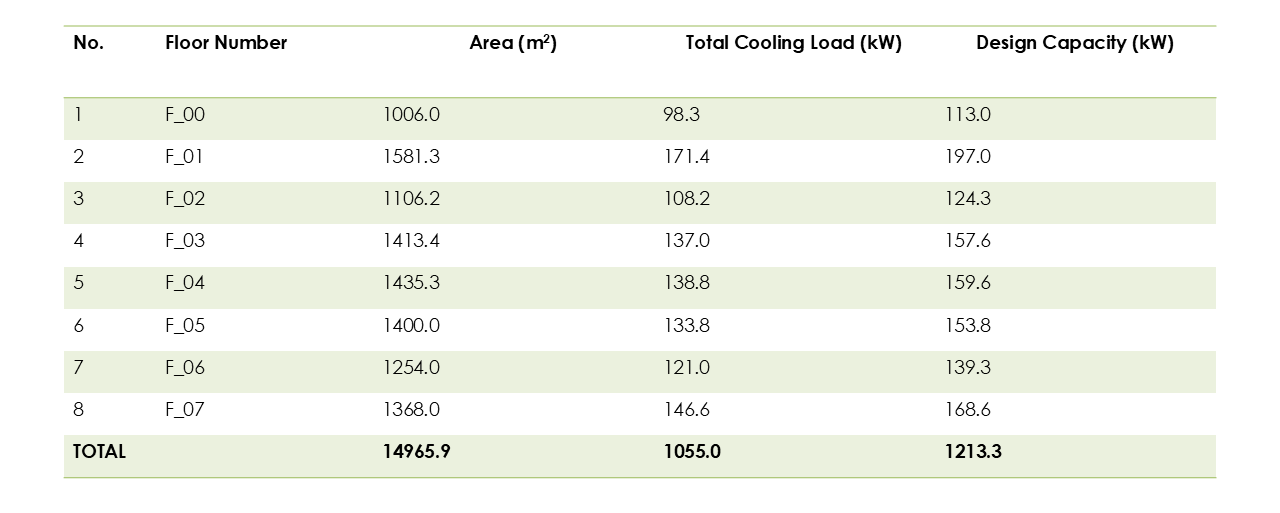

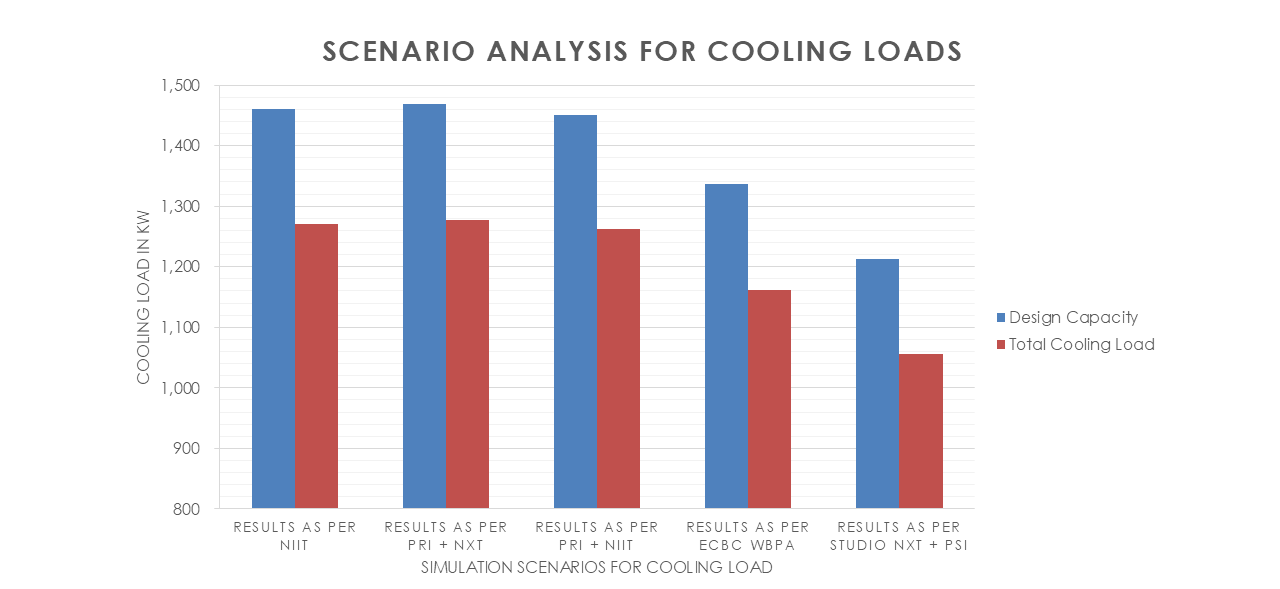

Performance Outcomes – Data-Driven Results (Cooling Loads And Comfort Gains)

The NIT, as prepared by CPWD, had already estimated the cooling load of the building, and also suggested U-Values for the external envelope, which complied with the NBC 2016 & ECBC 2017. Their chiller sizing had yielded a capacity of 375 TR for the entire 17000 square meters, which amounted to a very efficient 487 square feet per TR of air conditioning. (Generally, a building that can climb upwards of 300 square feet per TR begins to break into the ‘high performance’ threshold.)

The façade’s key performance parameters include:

| Façade Element |

Value (Units) |

| Insulated Roof U-value | 0.3 W/m2.K |

| Overall Wall U-value | 0.3 W/m2.K |

| Glass U-value | 1.5 W/m2.K |

| Glass SHGC (effective) | 0.25 |

| Ceiling/Floor Partition U Value | 2.27131 W/m2.K |

| Sky Light U Value | 3.40696 W/m2.K |

Several Sun path studies assisted the team to arrive at the optimal combination – cutting summer sun as much as possible (while keeping the design intent in mind), allowing winter sun in as much as possible, and creating optimal visual and thermal comfort conditions. A comparison of the iterations is as follows:

The combined effect was tangible: the building not only consumed less energy but also maintained a more stable and comfortable internal environment.

The façade’s performance validated its conceptual promise-a system where design itself became the first layer of energy efficiency.

Key Learnings For Practitioners

The GST Bhawan’s success offers clear takeaways for façade professionals and architects working in similar climatic contexts:

- Integrate Performance Early – Running simulations at the concept stage prevents costly redesigns and aligns aesthetics with science from the outset.

- Favour Passive Over Technological Fixes – Recesses, chajjas, and fins often outperform expensive double-glazing or films in India’s solar-intense climates.

- Collaborate Across Disciplines – When architects & engineers iterate together, the façade evolves as a living system rather than a late-stage correction.

- Design For Context, Not Template – Composite climates like Ghaziabad require hybrid responses—no single façade type fits all orientations.

- Think Lifecycle – Shading devices protect glazing, reduce maintenance, and extend material longevity, ensuring lower operational costs and embodied impacts.

As India adopts stricter energy codes and ESG benchmarks, such data-driven design will increasingly distinguish façades that merely look sustainable from those that truly perform sustainably.

The Aesthetic Of Performance

The GST Bhavan façade now stands as more than an administrative landmark-it is a proof of concept that aesthetics and sustainability can co-evolve. Its barcode pattern is both symbolic and performative, an identity born out of environmental intelligence.

By allowing data and design to speak to each other, the project demonstrates how iterative façade optimisation can transform a government office into a responsive, climate-attuned example. It offers a model for public architecture that is not only accountable in function but expressive in spirit.

Ultimately, the CGST Bhavan reminds us that architecture need not choose between expression and efficiency. When designers and contractors embrace analysis, the building itself begins to think—and, in doing so, to breathe efficiently, elegantly, and sustainably.

Quick Facts:

|