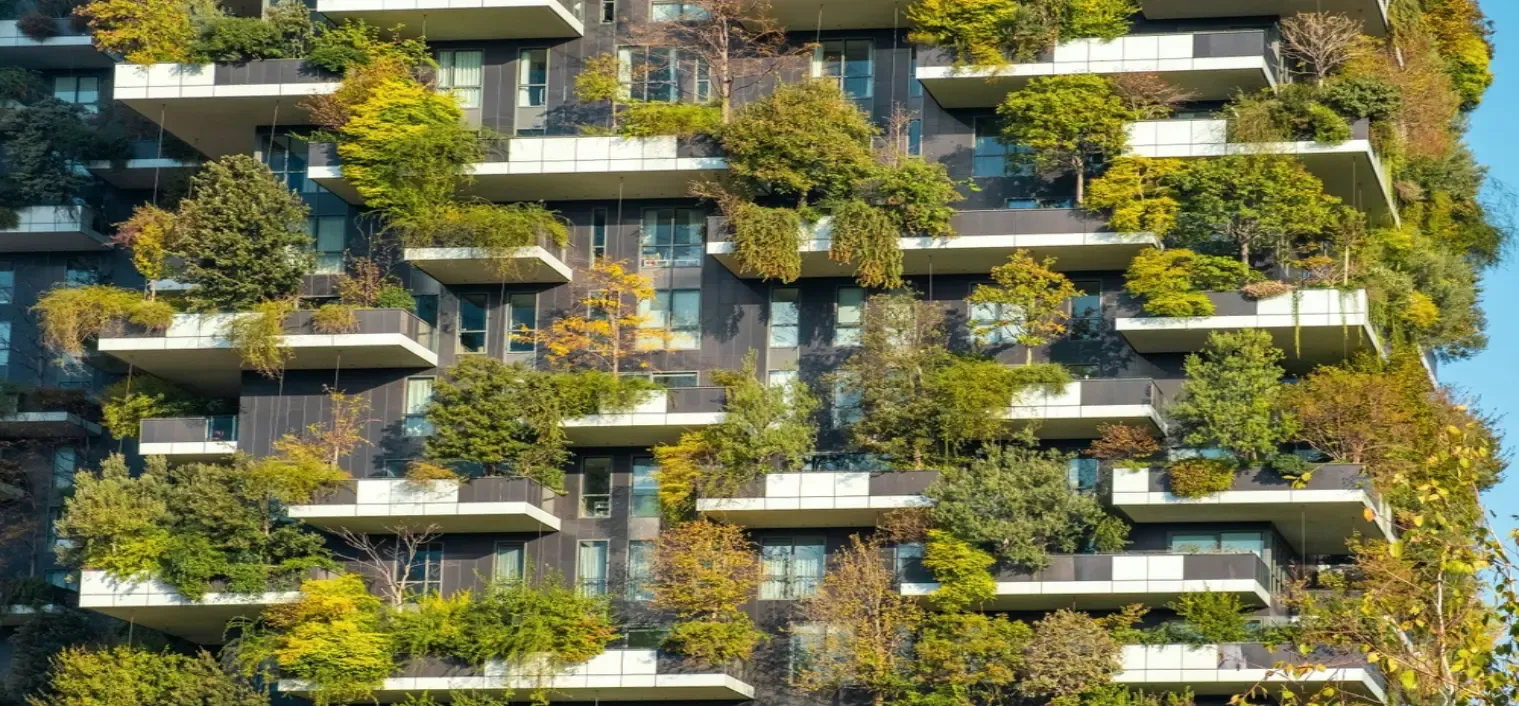

As our cities grow denser and hotter, we find ourselves in urgent need of building solutions that do more than merely contain people and activities – they must contribute positively to the environment. One such innovation at the intersection of architecture, ecology, and sustainability is the bioreceptive façade.

These building surfaces are not simply passive shells but active partners in urban health, designed specifically to support non-invasive plant and microbial life, particularly mosses, lichens, and certain algae. Unlike traditional green walls that require structural support systems, irrigation, and maintenance, bioreceptive façades invite nature in by design – from the microtexture of materials to their porosity and mineral content.

From Concrete Jungle To Urban Ecosystem

Urbanisation often replaces green space with impermeable surfaces that reflect heat, block water infiltration, and isolate us from the natural world. Bioreceptive façades flip this script by transforming buildings into microhabitats that:

- Reduce the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect by cooling surfaces through evapotranspiration and shading.

- Enhance urban biodiversity by creating hospitable conditions for mosses, lichens, insects, and birds.

- Capture airborne pollutants and CO₂, contributing to improved air quality.

- Encourage rainwater absorption and passive cooling.

- Improve mental well-being by integrating biophilic design into dense urban cores.

In short, these façades offer cities a layer of natural infrastructure – a living skin that performs ecological functions once confined to parks and green belts.

Engineering Materials For Life

The key to a successful bioreceptive façade lies in material science. Researchers are developing new types of concrete and ceramic composites with specific mineral compositions, surface roughness, and porosity optimised for colonisation. Unlike regular concrete, which is often hostile to plant life due to its high alkalinity, these new materials strike a balance between durability and ecological hospitality.

Examples include:

- Moss-friendly tiles with micro cavities and water-retaining capabilities.

- Recycled aggregates that mimic natural rock substrates.

- Additive-manufactured modules with parametric designs that control moisture, shade, and light exposure for optimal growth.

No Watering Required

One of the strongest appeals of bioreceptive façades is their low maintenance and passive operation. Because they rely on naturally occurring wind, rain, and sunlight, they are particularly suited for retrofitting existing buildings or enhancing infrastructure such as noise barriers, retaining walls, or parking garages.

Unlike conventional green walls, they do not require constant irrigation systems or structural anchors, making them cost-effective and scalable for wide deployment.

Obstacles To Overcome

Despite their promise, bioreceptive façades face several challenges:

- The speed of colonisation can be slow and climate-dependent.

- Aesthetic unpredictability may deter developers or planners.

- Long-term monitoring and performance standards are still evolving.

- Building codes and zoning regulations may not yet accommodate or incentivise these systems.

To truly realise their potential, we need partnerships between urban planners, ecologists, architects, and materials scientists, alongside policy frameworks that reward multifunctional design.

A New Relationship Between Buildings And Nature

In a world facing climate instability and biodiversity loss, we must move beyond buildings that are merely sustainable in energy terms and towards structures that are ecologically generative. Bioreceptive façades point towards this future.

Imagine a city where every wall is a mossy canvas, where even highway embankments contribute to biodiversity corridors, and where our architecture heals rather than harms. With thoughtful design and sustained investment, we can transform our cities from sterile boxes into living systems.