At The Threshold Of Change

For much of architectural history, façades have been treated as surfaces – sometimes expressive, sometimes passive, but almost always static. Yet today, as climate realities intensify and cities become increasingly fragile ecosystems, we are being pushed to rethink the building envelope not as a line of defence, but as an active participant in environmental performance.

As a landscape architect practising in India, I have often found myself working at the edges – where built form meets terrain, where inside transitions into outside. And in those edges, I see immense potential. The future of façade design, I believe, lies in embracing the logic of living systems, the rhythms of landscapes, the intelligence of ecosystems, and the adaptability of natural forms.

The Façade As A Living Interface

In nature, it is the edges – riverbanks, forest fringes, tide pools – that host the most diversity and transformation. They are zones of negotiation and exchange. What if our buildings could operate in the same way?

Rather than treating façades as barriers that separate us from the outside, we should begin to design them as living interfaces – membranes that regulate, breathe, and evolve with changing climatic and urban conditions. This shift from façade-as-object to façade-as-ecosystem could be one of the most meaningful transitions in sustainable design thinking.

Learning From The Landscape

In my practice, I have seen how landscape design often brings a systems-thinking approach to architecture. We think in terms of flows – of water, wind, energy, and experience. This perspective is urgently needed at the level of façades and fenestration.

Green façades, for example, are no longer merely aesthetic gestures. In our hot and humid Indian climates, planted façades can reduce solar heat gain, filter dust and pollutants, support biodiversity, and even enhance mental well-being. But we need to go beyond the idea of simply adding plants to walls.

Can a façade be designed to respond like a living terrain – absorbing monsoon water, channelling ventilation, and even harvesting energy through organic processes? These are not far-off dreams. They are questioning whether new materials, climate data, and integrated design approaches are beginning to address.

Examples That Inspire

Globally, a few path-breaking projects have already begun this journey. The BIQ House in Hamburg, Germany, uses algae-filled panels on its façade – not just as shading devices, but as mini bioreactors that capture carbon and generate biofuel.

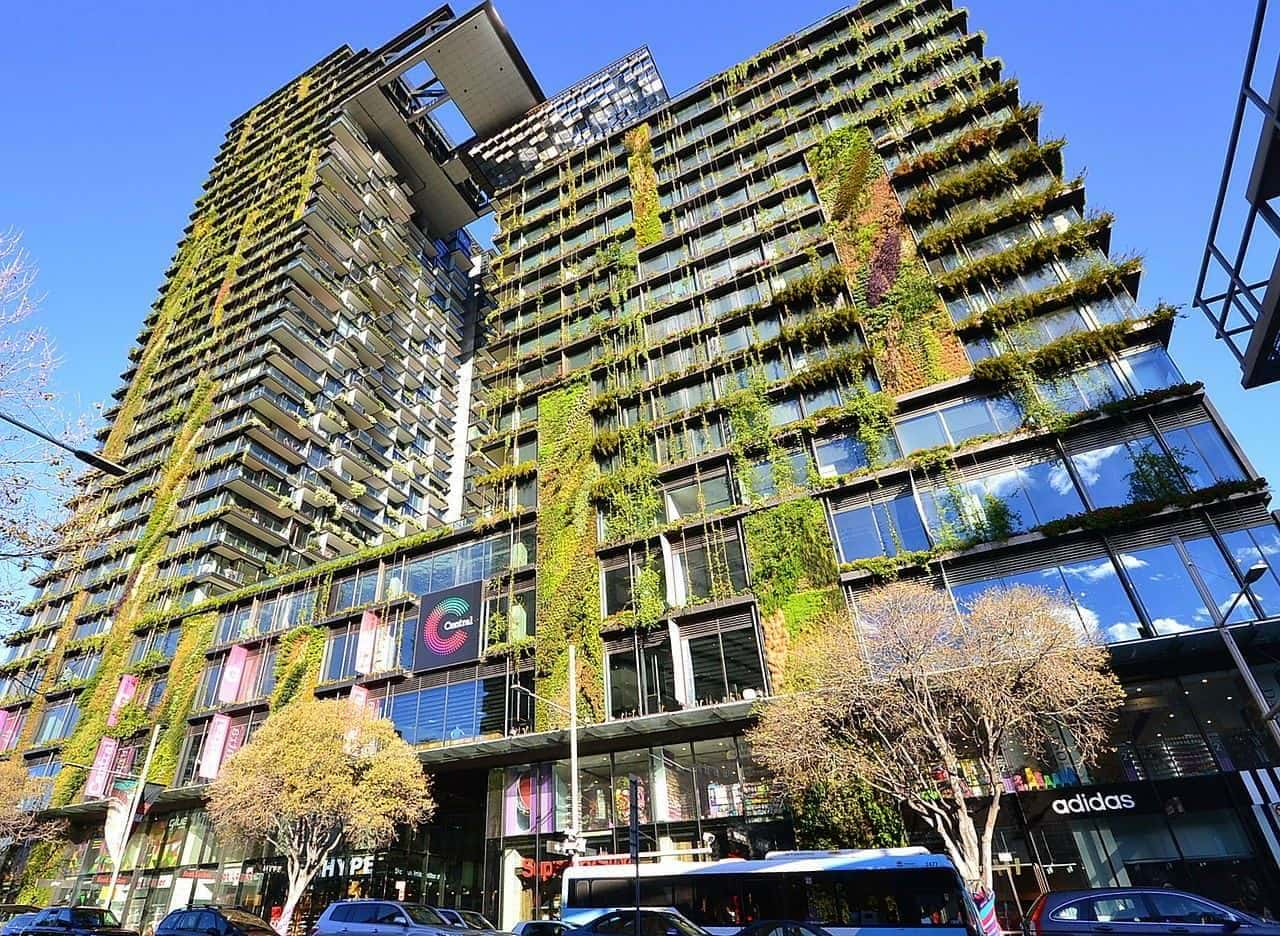

Closer to home, projects such as One Central Park in Sydney demonstrate how vertical gardens – designed in collaboration with botanists and horticulturists – can function as thermal buffers, habitat layers, and visual filters in densely populated urban areas.

While these examples may seem technologically ambitious, they offer a blueprint for how we can begin to imagine façades as productive systems. In the Indian context, I believe we have a unique opportunity to take this further, drawing from vernacular wisdom, tropical biodiversity, and low-tech ecological solutions to create living skins that are both affordable and regenerative.

Windows That Breathe, Openings That Adapt

If façades are the skin, then fenestrations are its pores. And just like in leaves, where stomata open and close in response to environmental cues, our windows and shading systems can be designed to breathe with the building.

Smart glazing technologies, such as electrochromic glass, already allow windows to adjust their tint based on solar exposure. But we don’t always need high-tech solutions to be climate-responsive. In many parts of India, we have long used jali screens, chajjas, and vegetative shading to cool and filter sunlight naturally.

What is needed now is a hybrid approach, where traditional strategies meet data-driven adaptability.

Imagine fenestrations that open based on humidity levels, or screens that filter daylight the way trees filter sun through their canopies. These are not just efficient – they are poetic.

Water, Carbon & The Vertical Terrain

In landscape, we work with the ground. But façades are becoming new terrains in themselves – vertical grounds that can slow stormwater, purify air, and even sequester carbon through materials like bamboo composites, algae panels, or bio-based plaster systems.

Think about this: a modular, planter-integrated façade system that serves multiple functions – shade, water collection, and even small-scale food production. While the idea can still evolve, the intent is clear – façades must start doing more. And with every climate event we face, this need becomes more urgent.

The Role Of Nature In High-Density Urbanism

In our rapidly densifying Indian cities, where open space is shrinking, façades might be the only place left to “grow” green. But it’s not just about adding foliage; it’s about restoring ecological value.

A façade that supports pollinators, cools the air, buffers noise, and offers residents a view of something alive—this is no longer a luxury. It’s a public health and sustainability imperative.

Projects like Bosco Verticale in Milan, or even smaller local experiments in Bengaluru and Mumbai, where green screens and planter modules are used in housing projects, point to the immense potential for vertical ecosystems in urban design.

Barriers To Break, Opportunities To Seize

Of course, there are challenges: maintenance concerns, budget constraints, and material durability. But these are all solvable – with the right collaborations, long-term thinking, and a willingness to experiment. We need more interdisciplinary work, where architects, façade consultants, ecologists, horticulturists, and landscape designers all sit at the same table.

And we need policies and incentives that reward performance over appearance – ones that prioritise functioning green systems rather than greenwashing. In India, especially, we can look to our vernacular roots and tropical intelligence to develop solutions that are uniquely suited to our context – affordable, adaptive, and alive.

Conclusion: Growing The Future

Ultimately, the future of façades will not be built – they will be grown. They will not just shield us from the environment – they will help us live with it, and perhaps even heal it.

As designers, our role is shifting. We are not just shaping form – we are curating relationships: between climate and comfort, between technology and tradition, between built surface and living system.

The façade is no longer a wall. It is a skin. A terrain. A threshold. A possibility.

Let’s begin to design it that way.