In the realm of architecture, the building envelope or the façade is increasingly becoming the most important component with regards to building performance and architectural design. As a synthesis of building elements, the façade acts as interface between the interiors and the exteriors. Thus, the manner in which we design this spatial boundary—to enable a seamless transition between two disparate environments is of critical relevance.

For a multi-storeyed building, if we were to set aside the highestfloor or roof and conduct a solar insulation analysis (a study that quantifies the solar exposure incident on the building), we would observe that the lower floors receive solar exposure only from the façade. Hence, the façade acts as the only potential source of external heat gain from the sun and from conduction and convection through air. In this regard, façade treatment with respect to the climatic considerations is extremely significant, especially in urban centres and cities where land is expensive and building vertical is the only way forward.

St. Andrews Institute of Technology & Management – Boys’ Hostel Block GURUGRAM, HARYANA

The 60,000 sq.ft. boys hostel building at the St. Andrews Institute of Technology and Management at Gurugram by ZED Lab is a meticulously designed, well-engineered residential complex that obtains its character from the basic building block – the brick. The building maintains a strong horizontal emphasis and utilises a restrained material palette consisting of fair-faced concrete exposed in the robust supporting structure in the façade.

PLANNING AND DESIGN STRATEGIES

skin façade

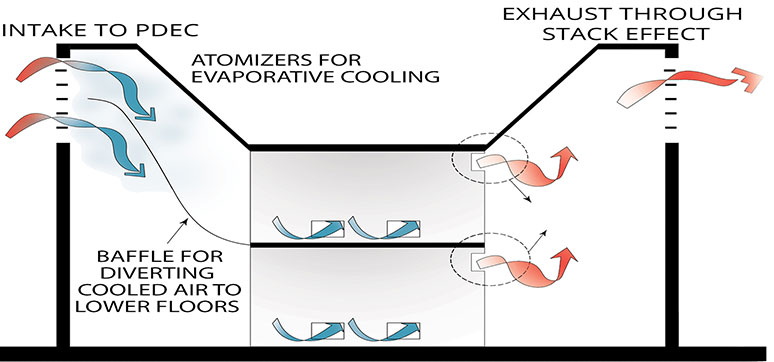

The boys’ hostel building reinterprets Indian vernacular architecture with ideas relevant to the present times and techniques. Anticipating the importance of student interaction with the spaces, the landscape around and amongst themselves, the galactic indoor spaces are design extensions of the exteriors. The layered interior planning of the building with passive design strategies facilitates comfortable intercommunication amongst the students. The contorted central atrium allows natural light to penetrate deeper into the building. It also acts as a solar chimney that takes away the stale and hot air within the building through the stack effect. The block accommodates residential units for 360 students with inclusive recreational courts and mess facilities.

The triple height spacious dorms depart from the conventional style of dorms, providing an enhanced user experience and a more expansive view of the outdoors to the students. The combination of the angled volume of the part ground floor and the linear shape of the first floor creates a shaded entrance (summer court) and an open terrace (winter court) on the south and north façades respectively. The interactive composition forms the social heart of the block, creating a stimulating experiential space for students to engage in discussions, socialise or withdraw from time to time. The landscaped ramp located within the summer court acts as a transition space between the harsh outdoor and relaxed indoors protfecting students from getting a thermal shock. This ramp leads to the light-filled cafeteria reinforcing the university’s focus on generous spaces for students to interact at a larger scale. The serendipitous creation of the winter court on the first floor in the north direction enables one to enjoy the weather during a summer evening and winter afternoons.

CONSTRUCTION METHODOLOGY

At ZED Lab, we believe that sustainability is not separate from design. Our teams thrive to design sustainable interventions as indispensable components that enhance the experience of the built environment. Therefore, factors such as the orientation of the building, materiality and creation of spaces in the hostel block derive existence through comprehensive research, based on climatic conditions, sun path analysis and air movement.

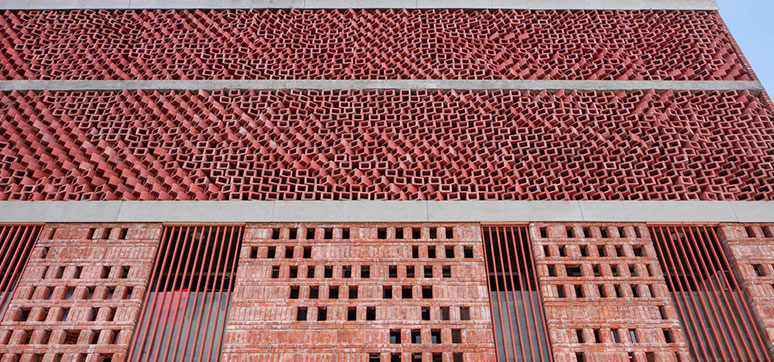

The use of software technology and computational studies is pertinent to the design of the brick jaali that circumscribes the building, providing thermal insulation and ingress of diffused natural light. The simulations or the parametric scripts designed using softwares and conclusions drawn from the analysis of climatic conditions discussed the existing radiation and the appropriate amount of radiation that should enter through the façade. Later running the simulations on each brick, we derived a composition that comprises arrangements/ layers of bricks rotated and then placed at regular intervals. Presently, the jaali profile and its composition are essential factors that reduce the heat energy of direct radiations by 70%, thus providing comfortable habitable spaces. However, the jaali also provides daylighting levels in the dorms equal to 250 lux.

QUICK FACTS:

- Project: St. Andrews Institute of Technology and Management – Boys’ Hostel Block

- Location: Gurugrm, Haryana

- Architect: ZED Lab Consultants – Structural – Design Solutions

- Contractors: Civil & Façades- LS Associates

CLIMATIC CONSIDERATIONS AS CLUES FOR FAÇADE DESIGN

The success of creating an effective façade lies in approaching its design through the lens of climatic considerations. To determine the nature of the façade for a specific climate, climate analysis exists as the only effective tool that can help provide clues with respect to façade construction and detailing. The analysis quantifies the level of solar, direct and diffused radiation incident on the exterior surfaces of the built form, which then serves as the foundation for the design of openings, shading devices, wall to window ratios, glazing specifications and the use of thermal mass based on humidity levels. Like most countries, India hosts a range of climatic typologies, from hot and dry, warm and humid, to cold and temperate. With the rise in altitude, there is a variation in humidity levels, air temperatures and the physical conditions of the environment. Accordingly, for the same design proposal, a difference in approach is required — four distinct façades would need to be developed to suit each of the above climatic conditions.

For instance, within the subcontinent itself, building façades in north-eastern India should be designed with light-weight materials such as bamboo and larger openings to maximise ventilation, while in Western India, where temperatures are extreme with a significant diurnal variation, thick walls with smaller openings are needed to block the heat during the day and provide insulation at night. Such a difference in approach to façade design can also adopted at the micro-level, across building typologies based on functionality and space use through the day.

radiation

For instance, in commercial buildings and offices occupants are largely working through the day and by night these buildings are left vacant. The façade should then be designed with the idea of creating day-lit interiors and enabling natural ventilation. In comparison, within residences, living areas and other common spaces are used more actively in the day, while at night the bedrooms are the most occupied. Therefore, façades for living spaces should be designed with adequate thermal mass to regulate high temperatures (for the north Indian summer, where temperatures range from 42-45 degrees Celsius) during the day and prevent heat gain, while façades adjoining bedrooms should be lightweight so that they can rapidly lose heat at night (where external temperatures range from 27-28 degrees Celsius in north India in the summer). Enabling such design strategies can go a long way in constituting energy-efficiency and reducing mechanical loads and costs in buildings. ‘

PARAMETRICISM’ AS AN UNTAPPED DESIGN TOOL

Conventionally, façade design iterations are modelled on their own accord, and environmental analysis tools are used for validation in the later stages of design. However, such a workflow creates a disconnect of energy optimisation between the façade and the internal built form.

In recent times, parametricism in India has been slowly echoing the theme of the modern architectural language. The term ‘parametric’ is derived from parametric equations which refer to the use of certain parameters that can be modulated to alter the result of an equation or a mathematical system. Through preliminary studies and analyses, façade requirements, say for a residence (the required penetration of solar radiation, size and nature of fenestration, material insulation etc.) are calculated. The façade is then designed using an integrated system that utilizes the environmental analysis and thermal mass optimisation backed by computational analysis. This is enabled through Rhino, Grasshopper and Ladybug (parametric design software based on algorithmic inputs that define design rules) through which a script is written to analyse the level of direct and diffused radiation on the primary façade. For instance, in a parametrically modelled brick façade, the radiation value of each grid cell on the façade then becomes the input for rotation angles of the brick in front of it. This reduces direct and diffused radiations by a significant amount on the principal façade and further prevents heat gain beyond the brick screen within the interiors.

MICRO-CLIMATE AS THE MISSING LINK

And while most architects and designers address climatic considerations within the sphere of façade and fenestration design, the relevance of the micro-climate is more often than not, sidelined. The micro-climate addresses the immediate neighbouring context of the building and site. While, we deliberate over wind direction and its impact on the façade, it often becomes irrelevant given the micro-climate and immediate site context of the building. Solar radiations too, will be significantly impacted in the presence of an adjoining tall structure that will provide shade and constitute a specific amount of solar reflection. Hence, the micro-climate and the context including the nature of the neighbouring buildings and their distance from the façade under consideration need to be analysed to effectively conceptualise a building façade.

THE RISE OF THE SECOND SKIN

In the past, the trend of the single skin façade—designed with a single-layered envelope of a permanent material such as glass, has dominated the skyline of a majority of cityscapes today. While modernist in appeal, such glass enclosures tend to act as solariums that trap heat and therefore add to mechanical ventilation and cooling loads. Further, the generic wall-window elevation does not do much aesthetically and the paint and plaster treatments on the walls require maintained and are not permanent solutions. Hence, looking at the second skin as a solution is becoming the most relevant and favoured alternative. In hot and humid countries, like India, the double-skin façade needs to respond to the climatic context through vernacular design. If we think about it, our country’s architecture has for centuries employed design mechanisms for energy efficiency.

We see the use of elements such as jaalis (latticed screens), chajjas (sloping eaves and canopies) and jharokhas (overhanging balconies), particularly in India’s northern regions addressed needs for lighting and ventilation while protecting occupants from harsh sunlight. While double skin systems in the West employ a double-glazed units with an insulation layer in between, such a solution will be of no value in the Indian context. Within the Indian context, the outer skin should be designed as a semi-permeable layer such as a jaali to help in shading and regulate the temperature between the exterior and interior environments via a controlled airflow. In this sense, this first skin becomes a transition zone on the vertical plane and creates an intermediate micro-climate of its own.

The role of the second skin, then, should be to provide a volume where the user can step out of from the interiors to a shaded environment such as a balcony or court but is a space which prioritises thermal comfort through the adaptive behaviour of the building and enables functionality. The second skin takes on the role of a breakout space between the interior and exterior. It empowers occupants to take charge of their environment and activity as well as connect with nature while still being inside the building.

St. Andrews Institute of Technology & Management – Girls’ Hostel Block

The Girls’ Hostel Block at the St. Andrews Institute of Technology and Management in Gurugram explores the intersection of education and sustainability through the lens of the vernacular. Completed in 2020, the design for the 25,000 sq.ft. Girls’ Hostel takes cues from the adjacent Boys’ Hostel Block and is articulated in brick and fair-faced concrete, with exposed structural members abutting the structure along all sides.The hostel is home to 130 students, with dorm rooms spread across four levels in addition to hosting ancillary spaces like a pantry, recreational areas as well as social spaces. The ground floor comprises twelve doubleoccupancy rooms along with a double-height reception, pantry and indoor activity lounge.

CLIENT BRIEF AND CHALLENGES

The design faced a series of challenges from conception to execution. The primary design challenge was to create a secure hub for the girls, a campus within a campus fitting into the urban master plan that did not restrict the movement, while establishing a connection with the outdoors. In response to the constraints, the layout has been designed to incorporate indoor and outdoor spaces that connect physically and visually at different levels to enhance interactions and social activities. The students have been given the freedom to create their own space in a safe environment, without any imposed restrictions.

DESIGN AND PLANNING

The design seeks to reinterpret conventional standards of human comfort through introducing the idea of adaptive comfort — the principle that people experience differently and adapt, up to a certain extent, to a variety of indoor conditions, depending on their clothing, their activity and general physical condition. The building unfolds as a series of multidimensional spaces, arranged in a hierarchical order through the method of adaptive layering. As students move from the interiors of the building into the open, they experience distinct transitions in varying thermal environments. The design of the building is kept simple while identifying essential elements like the staircases as hubs for social interaction. Transitional and circulation spaces such as bridges open into lounges and pause points to create room for socializing and group study.

THE DOUBLE SKIN FAÇADE

With limited space available along the northern façade of the hostel, a double-skin façade has been developed with the intention of creating a semi-permeable layer that would help in shading and regulating the temperature between the exterior and interior environments via a controlled airflow. The parametric screen takes cues from the previously developed façade that spanned the adjacent boys’ hostel within the institute. For the girls’ hostel, the exterior façade screen uses hollow pigmented concrete blocks to resemble the colour of the red brick. The blocks have been successful in addressing three concerns. Not only do they provide adequate thermal mass to absorb the heat, but with a depth of eight inches, the direct radiation has to penetrate through several layers within the block and gets reflected on different surfaces multiple times before entering the interiors reducing glare. In addition, since the block is penetrable, the air volume passing through this mass loses its heat through compression on the basis of Bernoulli’s principle. The blocks are also slightly rotated at a specific angle based on the insulation analysis with respect to solar heat gain.

LANDSCAPE STRATEGIES AND WATER MANAGEMENT

The landscape design enriches the space by bringing the greenery inside to serve not only aesthetic but also functional purposes. The edge details of the planters are designed as seaters, allowing students to sit with nature. The peripheral areas feature bamboo that creates a screen. Outside the building, champa trees have been planted due to their large canopies to create shaded seating spaces. The surface of the outdoor landscaped court is penetrable, facilitating ground water penetration. The wastewater such as water from the washrooms is conveyed to the sewage treatment plant and is reused for horticulture purposes.

SUSTAINABILITY AND ENERGY EFFICIENCY

The Girls’ Hostel building is an exemplar of sustainability through its energy efficient design. The double-skin facade acts as thermal mass, reducing the incident direct and diffused radiations by 70% on the principal façade, thus, minimizing heat gain within the habitable spaces behind the block wall. This further reduced the mechanical cooling loads by 35%, a marked increment from the Energy Conservation Building St. Andrews Girls Hostel – Pigmented hollow block parametric façade Code base case of public buildings.

THE FUTURE OF THE FAÇADE

While ratings such as The Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC) and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) recognise green building certification systems, providing verification that a building or community was designed and built using strategies aimed at improving performance, their interpretation for façade design remains largely unexplored in India.

Presently, innovations in façade design across the Indian landscape are limited to the use of double-glazing and cavity walls as strategies for energy efficiency; however, these may not always be effective and resilient in the long term. One solution that shows promise is designing façades as living environments with habitable spaces. To achieve mean temperatures, these spaces can integrate cooling systems by taking the return air from internal air-conditioned spaces through the façade skin, and back into the Air Handling Units (AHU). The future will see façade design move towards leveraging computational tools to develop environmentally compatible and economically viable systems that are designed to be in tune with nature and optimised for energy savings.