The structural design of stone cladding is becoming more and more present in façade engineering. The designer needs to deal with natural material and therefore with the uncertainty of its structural behaviour. Stone has historically been used in load-bearing walls because of its high compression resistance. With the new requirements of slim and tall buildings, the stone became obsolete as a structural element and new materials took over such as reinforced concrete and steel. This required a new way of using stone to obtain the aesthetic effect of a stone wall in highrise buildings. To achieve this, the stone is cut into slabs of various thicknesses and installed in cladding panels using various supporting systems.

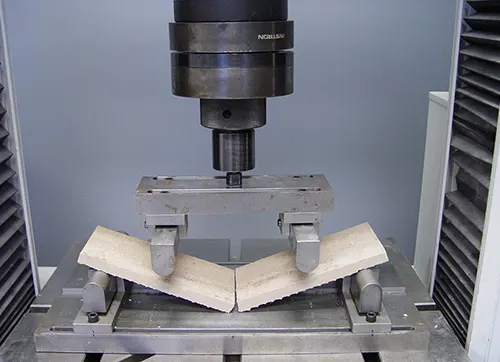

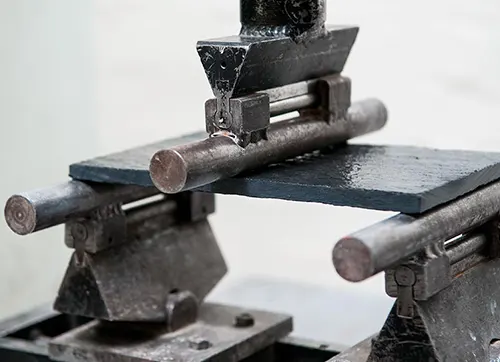

Testing the stone used on each project is a good practice to avoid unexpected structural failures of the panels. The designer shall keep in mind that stone is a natural material, and therefore its performance cannot be engineered such as aluminium and steel. Different types of stones show different structural behaviour.

Based on the origin: some are more reliable, such as granites and marbles, and other less reliable, such as limestones and other sedimentary stones. Limestones are usually presenting inclusions and therefore weak spots in the material itself. In terms of reliability, the standard deviation of the test results changes based on the type of stone.

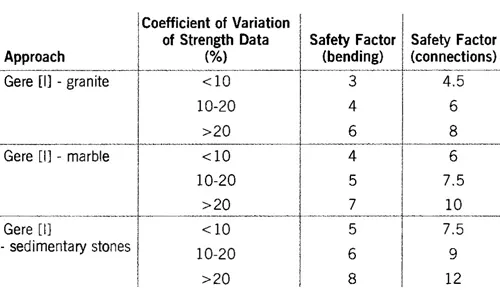

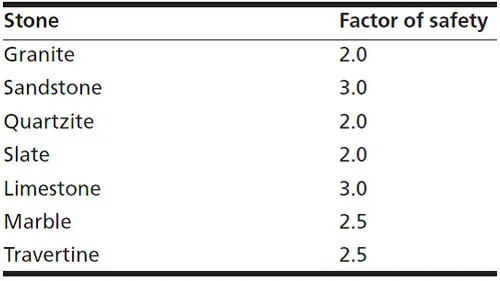

The table below shows advised safety factors to be used based on the material and the coefficient of variation of the bending resistance. (Please note that these safety factors are based on American standards and therefore should not be used when designing according to Eurocodes). As is shown, and expected, the safety factors increase with the coefficient of variation of the resistance. This means that the stone panel is less reliable in terms of structural performance. In addition to that, the type of stone influences the safety factors. For sedimentary stones, higher values are advised than for granites and marbles. This is due to the reliability of the material itself

The same principle is used for well-known construction materials such as steel and concrete. This is based on the reliability of the material to be consistent with the resistance shown during tests. In the same way, the different stone reliabilities are considered. As an example, the concrete has a higher safety factor than steel or aluminium, due to the fact that concrete goes through a production process that is less controlled compared to metals. In addition to that, concrete is a mixture of materials and may include weak spots due to bigger localised aggregates that steel does not have.

This is acknowledged in the BS 8298-4, “Commentary on 6.1.4” where the safety factors in Table 1 are advised to be applied to the lowest expected flexural resistance value according to EN 13161. The minimum expected value is the 95% percentile of the resistance statistic distribution, therefore, the characteristic value described in the Eurocodes. This approach is the one advised when applying this code to design stone cladding panels. The standard presents another statement in the commentary and is reported below: “If the test is undertaken with dry stone, and the mean strength calculated, the factor of safety based on that mean strength, and the ultimate design load, ought to be 5.0, regardless of stone type.

Alternatively, if additional tests are undertaken with saturated stone (minimum ten specimens) and the wet mean strength calculated, the factor of safety may be reduced to 4.3, based on the ultimate design load regardless of stone type.” It is clear that this methodology can lead to the under-design of stone panels, especially when applied to sedimentary stones. Due to the high coefficient of variations obtained when testing such stone panels, sometimes a higher safety coefficient shall be used than the ones shown in the statement above.

The recommendation when designing stone panels is therefore to double-check both cases: safety factor on mean value resistance and safety factor on minimum expected value. In addition to that, the coefficient of variation shall be considered in the determination of the safety factors to be used. Further guidance in stone structural design using the Eurocode semi-probabilistic method can be found in the ETA11/0145 and Dimension stone design –partial safety factors: a reliability-based approach by Rui S. Camposinhos PhD.