HOK’s Circadian Curtain Wall concept draws on biophilic design to offer building occupants abundant natural light while minimising solar heat gain. How can façade systems play a more important role in improving employee health and well-being? That was the challenge in a recent competition, and it got me thinking about an idea. For the past two years, me and my colleagues in HOK had been working on a concept for a load-bearing façade for high-rise buildings.

That design of structural exterior enclosure, replaced much of the aluminium found in modern curtain walls with steel, giving the façade additional strength to serve as part of the building’s overall framing and, because steel requires one-third the amount of carbon to produce as aluminium, reducing its embodied energy.

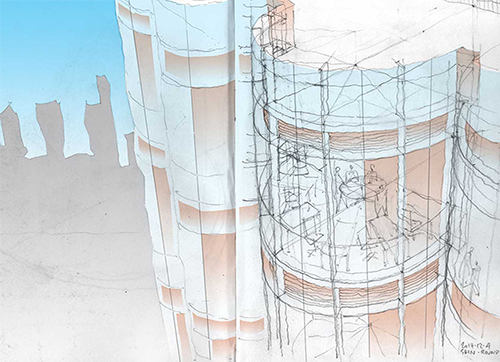

More recently, I have been toying with a further evolution of the concept: What if curved glass could also reduce the use of aluminium while giving the building skin more strength and wind resistance? I was playing with this idea of curved bay windows and putting them into clumps where you have curve atop of curve in a kind of fractalian pattern.

And it struck me that such a curved glass façade also spoke to the design brief. It extends the indoors outside and creates an office environment with elements from nature that we know contribute to health and wellness. Thus was born the Circadian Curtain Wall.

Geometry Inspired By Nature

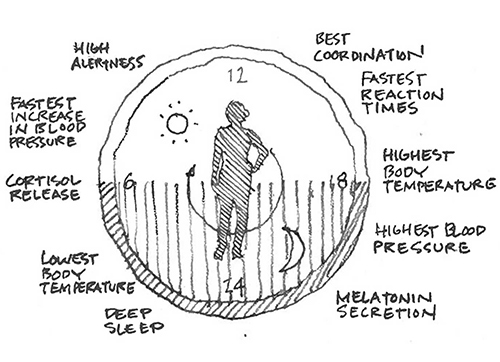

As its name suggests, the Circadian Curtain Wall draws on the very real connection humans – and all living organisms – have with the daily cycle of daylight and darkness. The façade’s bubbled glass offers wide-angled views to the outdoors and brings natural light deep into the building, keeping occupants synced to the circadian rhythm of night and day. Natural light and views are also key components of biophilic design that have been shown to boost performance and general happiness.

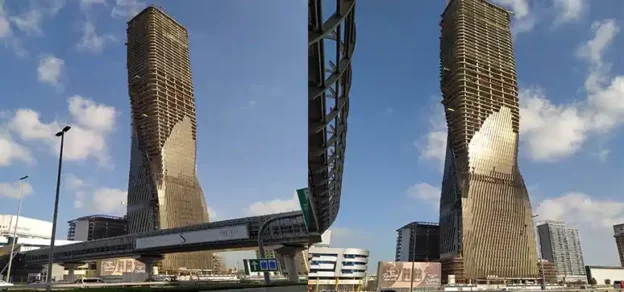

Biophilia plays into the design in other ways, too. The design competition challenged participants to imagine a façade for a proposed 30-story office building on a waterfront site. HOK’s concept, submitted with assistance from WSP Built Ecology, imagined the building with an ovoid floor plate that, with the addition of the convex curtain wall glass, would create a flower-like organic geometry.

The enclosure and building form are shaped in response to the path of the sun both discreetly at each window and overall across the oval floor plate. You can follow the sun around the footprint of the building somewhat like the hand of a clock. The circular geometry of the windows and the floor plan follows the cycle of the circadian rhythm.

Within office areas, the façade’s bay windows serve to extend the interior out past the building’s main footprint, allowing office workers to surround themselves with views and natural light. Dual atriums on the north and south of the building further connect building occupants to nature. In contrast to the office bays, these spaces bring the outdoors into the building, playing host to distinct plant life in a semi-conditioned space. Flora in the north atrium include species that thrive in low light, whereas plants in the south atrium feature full-sun varieties.

Passive And Automated Shading

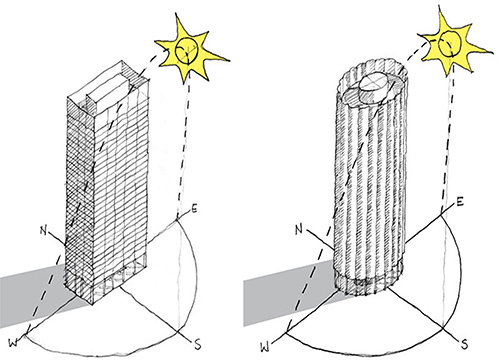

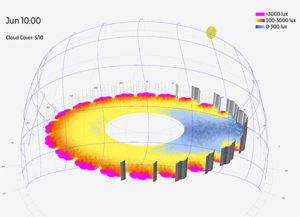

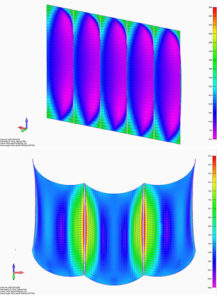

The Circadian Curtain Wall’s bulged windows provide external shading even on sides of the building exposed to full sun. At any given moment the tower to the right is 75 percent self-shaded, the one on the left 50 percent. As the sun moves around the building, the clusters of curved window bays limit the surface area exposed to direct sunlight and provide shading to adjacent areas of the façade. This design allows more natural light to enter the building and reduces the reliance on view-limiting window shades to control glare. Modelling analysis found the Circadian Curtain Wall’s natural shading also significantly reduces solar heat load when compared to a traditional building with a rectangular floor plate and flat façade.

The oval floor plate exaggerates this phenomenon, but I think the Circadian Curtain Wall could provide similar benefits if used on a rectangular building. The curvature of the glass means the sun is only hitting the windows at a right angle in a fairly limited area, and the windows’ convex shape is providing some shading elsewhere. Even with natural shading, building occupants will require additional sun filters. To address this, the design team proposed automated shades in a ventilated six-inch cavity between an exterior piece of glass and insulated glazing along the interior of the building. The shades protect each bay window from direct solar gain and glare at all times and automatically open and close in response to the sun’s location and intensity.

Housing the shades within a vented cavity supplied with filtered air keeps them clean and reduces maintenance costs, while automating them increases the amount of natural lighting within the building and reduces energy use. In making them mechanical, the design also eliminates human error, i.e. people’s tendency to draw the shades and then forget to open them when the sun is no longer a factor.

A Peek Behind The Curtain

The Circadian Curtain Wall offers several other advantages over traditional building envelopes. The concept’s double-skin façade, for example, provides the building with an extra level of thermal and sound insulation.

Additionally, the cavity between the outer and inner glass could be used to create a Trombe Wall effect where solar-warmed air within the cavity is used to heat the building during the winter or siphoned off to reduce cooling load during warmer months.

Trombe Walls were popular in the 1970s when a lot of hippies – including my parents – were building solar houses in places like New Mexico where I grew up. That background notwithstanding, they are a simple and effective form of passive solar energy that could be used more widely for heating a building in cooler months and shedding heat or storing it for night-time in the summer. In using curved glass, the Circadian Curtain Wall also has much greater inherent strength and stiffness than it would with traditional flat-panel glass (though the glass is not safe to augment the building’s primary bracing). Wind-load analyses (below) suggest that the curved glass acts as a beam spanning floor to floor and could eliminate the need for supportive mullions every five feet as in most conventional curtain walls.

Convex glass panels measuring 10-by-15 feet could be connected with structural silicone with only a slight aluminium frame needed to house the internal shading units. In eliminating the supportive mullions, My team estimates that a 30-story building like the one used in the design competition could save 300 to 400 tons of aluminium in 300,000 square feet of skin compared to a conventional curtain wall.

Promising Results

Circadian Curtain Wall grew from an abstract idea to a detailed concept in just a couple of months. Though the design team is now refining some of the façade’s initial assumptions and ideas, the initial analysis of the curtain wall has been encouraging. Day lighting and energy model simulations (above) conducted by WSP Built Ecology found that the system could reduce energy use by 16 percent, peak cooling load by 24 percent and peak heating load by 27 percent in a 30-story building. Those are significant amounts. Intuitive belief, knowledge about people’s innate need to connect to nature and results from early modeling suggest that Circadian Curtain Wall is a concept worthy of further exploration.