On 14 June 2017, the city of London woke up to the tragic news of a devastating fire that ravaged a high rise apartment in North Kensington – the Grenfell Tower tragedy, the deadliest residential fire in the United Kingdom since the Second Worldwar. Since then, it has been the subject of detailed investigations, elaborate media coverage, comprehensive analytical reports as well as numerous conspiracy theories.

The 24-storey residential building, originally built in 1974, consisted of 129 flats that provided social housing. In 2016, a refurbishment of the tower was completed during which new exterior cladding was installed and the windows and heating systems were replaced. Though a criminal investigation of the fire is still underway, some reports have isolated the reasons for the rapid and almost undeterred spread of the fire across the façade of the building. Most reports connect the fire with serious lapses in the quality of the renovations completed in 2016.

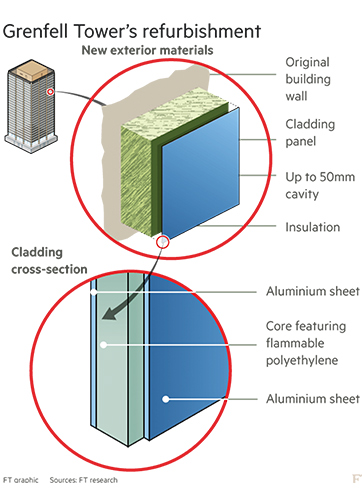

A BRE (Buildings Research Establishment) Report submitted to the Metropolitan Police Service in January 2018 indicates that the polyethylene core of the Aluminium Composite Material (ACM) cladding used, installed in the 2016 refurbishment, could have ignited, causing the fire to spread. Another report (the Grenfell Tower Inquiry Phase 1 – Final Expert Report, 21 October 2018) by Professor Luke Bisby of University of Edinburgh also states that the “the primary cause of rapid and extensive vertical and horizontal external fire spread was the presence of polyethylene filled ACM rain screen cassettes in the building’s refurbishment cladding system and in the architectural crown detail”.

Fig. 3 : The Address Downtown Fire in Dubai (2016)

Fig. 3 : The Address Downtown Fire in Dubai (2016)

The Grenfell Tower fire is only one in a number of major fire outbreaks that have taken place in high-rise buildings around the world in recent times. Worryingly, out of the 11 major fire outbreaks reported from around the world in the last decade, 9 seems to have happened due to the indiscriminate usage of polyethylene core and inflammable cladding.

Another unsettling fact is that 5 of these major 11 fire incidents in last decade occurred in Dubai – the Address Downtown in 2016, the Marina Torch in 2015 and again in 2017, the Tamweel Tower in 2012, and the Saif Belhasa Building in 2012. Many of these fires are being attributed to the usage of exterior paneling that is not fire-resistant. The Dubai story serves as a grim reminder of the fact that as the global hunger for new building stock fuels the rapid pace of construction of new high rise buildings, fire-safety norms might get compromised.

However, tragedies of this scale should serve as clarion calls for the international building and construction industry to study closely the reasons behind such fire incidents and adopt appropriate measures to avoid escalation of risks to fire-safety. The need to design fire-resistant building façades, particularly in high-rise buildings, cannot be stressed enough.

While the building façade serves as an essential envelope that protects the building from the elements, the façade also represents one of the most vulnerable elements of the building, particularly in the event of a fire. With the green building practices becoming ‘more mainstream’, what appeared earlier to be an uphill battle against unsustainable building practices seems to be nearing an end – more attention is being paid to the thermal performance and energy efficiency of building façades.

The building industry is increasingly favouring the use of light weight materials that are energy-efficient to minimise the loss or gain of heat through building façades. However, while there is a discernible global shift to make buildings more energy efficient through the adoption of green building practices, hastily executed plans to meet energy efficiency standards can have unintended and at times tragic consequences.

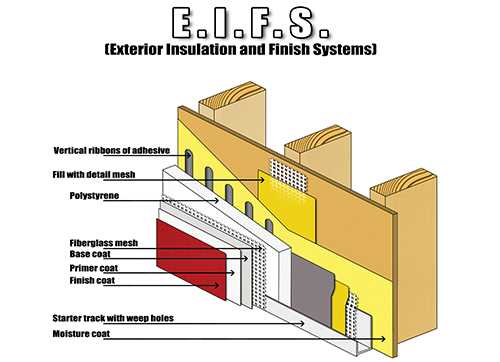

A 2012 report commissioned by the Fire Protection Research Foundation (FPRF), USA identified several commonly seen challenges to fire-safety posed by existing green building systems of construction, including lack of reporting systems that flag probable causal links between certain fire incidents and green buildings; risks to fire-safety posed by certain ‘green features’ and ‘green materials’ including fire outbreaks connected to solar panels; fire hazards related to the usage of certain energy-efficient insulation materials and external cladding; and the fire resilience of buildings having timber frames and lightweight engineered lumber (LEL) components.

The report also makes an assessment of the fire-safety concerns linked to various green building elements and identifies elements that are associated with:

• High levels of risk: (i) Structural integrated panel (SIP) (ii) Exterior insulation & finish system (EIFS) (iii) Rigid foam insulation (iv) Spray-applied foam insulation (iv) Foil insulation systems (v) Area of combustible material used in façades;

• Moderate levels of risk: (i) High-performance glazing (ii) Low-emissivity & reflective coating (iii) Double-skin façade (iv) Bamboo, other cellulosic (v) Vegetative roof systems (vi) Area of glazing in façades;

• Low levels of risk: (i) Biopolymers, FRPs (ii) PVC rainwater catchment (iii) Exterior cable/cable trays (iv) Awnings on façades (v) Exterior vegetative covering on façades.

A review of various green certification systems and codes such as International Green Construction Code (IgCC), LEED, BREEAM, etc. indicates that, with the exception of a few codes such as the rating system of the German Sustainable Building Council (DGNB) and BREEAM In- Use, most green rating systems have not explicitly incorporated the fire-safety objectives within the scope of their ratings. While the DGNB rating system incorporates criteria for fire prevention, BREEAM In-Use includes fire risk reduction characteristics.

It is also problematic that certain materials that are highly rated for their energy efficiency characteristics present elevated risk levels as far as fire-safety is concerned. For example, vinyl and polymer-based building products such as vinyl sidings are rated highly by rating systems like LEED. According to LEED, vinyl and polymer based products are preferable as they use recycled content, minimise heat loss and gain, are durable, and are sourced locally. However, a study by Underwriters Laboratories Firefighter Research Institute shows that vinyl siding coupled with certain insulation materials present high risks to fire-safety.

Therefore, it is imperative that adequate attention is paid to how energy-efficient façades perform under critical conditions such as a fire outbreak. Fire incidents pose one of the most extreme load conditions for any structure. The structure’s ability to survive therefore depends on how well designed it is. As recent major fire incidents have clearly shown, façade design can have a great impact on the path and pace of fire spread. The authorities in the United Arab Emirates have estimated that there are at the least 30,000 buildings in the country with external siding that could potentially aid rapid fire spreads across building façades.

While the loss of lives in major fire incidents forces government authorities to revise and update fire-safety regulations, it is important that the construction industry is not left playing catchup to regulators revising fire safety norms. Governments can encourage this by incentivising the active adoption of building practices that go above and beyond the limits of the mandatory legal requirement for fire safety. Certification systems such as BREEAM In-Use already awards credits for proactive fire safety management beyond the minimum legal limits.

No designer should be made to feel that he needs to choose between fire-safety or sustainability – that you can only have one or the other but not both. Going forward, all green building certification systems must be updated to integrate fire safety objectives into the overall goals of sustainable design.