Nowadays, fire safety in façades is a recurring topic in the construction industry. We have seen many tragic incidents happening, especially in high-rise towers, where a fire in an apartment starts on a chain reaction in the whole building façade, leading to life loss and extensive damage to the properties. Notable examples are the Grenfell tower in London, Torre dei Moro in Milan and the Torch in Dubai.

If we investigate the reasons why this happens, the main issues are:

- Poor choice of materials used in the façades, allowing for combustible cladding or insulation

- Façade detailing, leaving the possibility of fire spreading between floors

- Incorrect site installation or missing components considered during the design phase

The surprising thing is that, usually, there are many stakeholders involved in the projects, from architects, project managers, fire engineers and, if we are lucky, façade consultants and capable contractors. So why is this still happening? The main reason for this is related to the local regulations that allow some types of materials to be used or for some specific façade details that are not reliable in terms of fire spreading between floors.

I have been told once by an experienced façade engineer that: “Regulations will change only when something really bad happens”. And this, in the case of the UK, where all regulations changed after the Grenfell Tower fire. The question we should ask ourselves as designers at this point is: could this be predicted? Could a better façade detailing have been considered? We will not find these answers in local regulations but what about other standards used in other countries? Could that help us improve our judgment by finding small details that will make us think: is this worth considering even if it is not there in our local regulation?

FAÇADE DETAILING

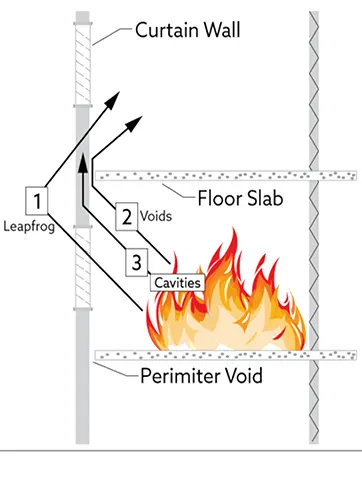

I would like to show an example I have experienced in my professional journey. As you may know, there are three ways how a fire can spread between floors:

- Leapfrog, breaking the external glass and jumping to the floor above.

- Voids between the curtain wall and the face of the superstructure slab

- Cavities within the curtain wall assembly

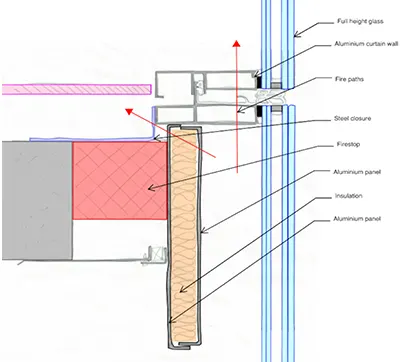

About 5 years ago, the detail is shown in Figure 3 – an aluminium curtain wall, vertical detail with a “bulkhead spandrel”- was easily allowed in the UK. In principle, the spandrel is recessed to provide an external full-height glass without a transom. During the design phase of the building, this was the preferred detail from the architect, but the comment I made as a façade engineer was that fire could spread between floors as the aluminium transom at the stack joint, in the event of a fire, would have melted and allowed the flame to get to the floor above. The answer I received was that the current regulations were allowing such detail as the façade had no requirements of being fire rated.

After the Grenfell fire, CWCT issued TN98, including some additional precautions to consider in façade detailing. The document showed the very same detail providing indications on including a steel sheet and plasterboard at the transom location to stop propagation between floors. While this detail was previously allowed in the UK, what are the requirements of other regulations in Europe? In Italy, as an example, there is a specific requirement on how to design façade interfaces with the structural slab.

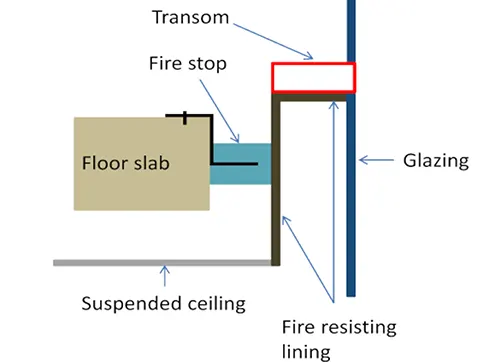

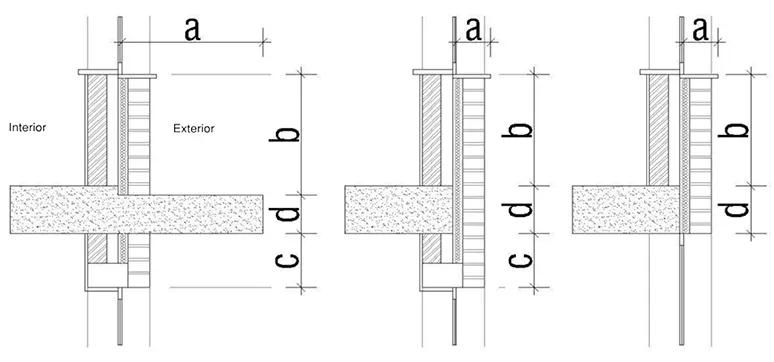

If you investigate Italian regulations, this detail could not be accepted as to avoid fire propagation between floors, an insulated fire-rated fascia of 1.0-meter minimum is requested to provide compartmentation. The diagram shown in figure 5 is extracted from the Italian guidelines of the requirements in façades to avoid fire propagation. The requirement is simply that the sum of the distances “a” + “b” + “c” + “d” should be not less than 1.0m. Each of these components shall achieve a fire resistance of EI60. A separate note says that, for a curtain wall, also the junction between the back of the spandrel and the face of the slab shall have a fire resistance EI60. The aim of this is to avoid the fire spreading for leapfrog or through voids.

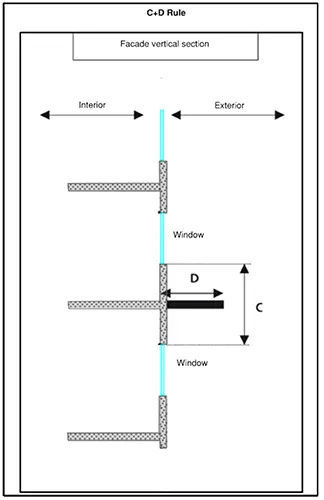

The same requirement can be found in the French standards, from the document “instruction technique n° 249 du 21 juin 1982”, where the same principle is followed. This is generally called the “C+D rule” and defines, in different cases, the minimum number as the sum of C+D. The minimum value of the sum of C+D is correlated to the combustible mass in the floors analysed. The more the combustible mass, the more height needed to be ensured. The requirement for the “C” part is very similar to Italian regulations as fire resistance of 60 minutes is required.

This regulation, also, provides additional precautions to be considered for the design of curtain wall systems:

- The bracket supporting the curtain wall shall be protected from fire through a fire stop or encased in incombustible insulation.

- A steel reinforcement within the curtain wall mullion at the spandrel area shall be provided. This steel profile needs to be directly fixed to the protected brackets.

- The backpan of the spandrel element shall be in steel, bent and fixed to the steel reinforcement in the mullion.

During a fire event, all these precautions allow to preserve the curtain wall bracket’s structural performance and support the fire-resistant spandrel element to allow for long-standing protection from the fire on the floor below and stop fire propagation. As is shown, the UK, Italian and French regulations are dissimilar from each other providing different requirements for the façade design, but the probability of a fire event and related damages are no different between countries. So why such differences?

FAÇADE MATERIALS COMBUSTIBILITY

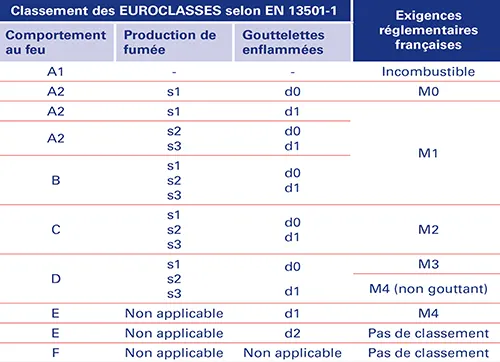

When we investigate combustible materials, then things change a bit. In Italy, the regulations were required only for insulation materials classified B-s3-d0 according to EN 13501. Some new regulations are being recently issued which will not be considered in this article. Regarding French standards before 2019, it is difficult to make a comparison as the products were classified according to NFP 92-501 and not EN 13501. As shown in figure 7, the classification M1 is a mix between A2 and B, therefore. It would be difficult to make a comparison of those requirements with the recent regulations according to EN 13501. Nevertheless, a new regulation dated 07/08/2019 for façades, including new requirements to limit fire spread between floors, is required to use materials with a minimum reaction to fire A2-s3, d0 from the 4th floor of buildings.

In the UK, before the Grenfell fire, materials used in façade ought to have at least a class B-s3, d0 according to EN 13501. Now regulations are very strict and for residential buildings above 11 m high, a minimum A2 s1, d0 is required.

A QUICK GLIMPSE INTO THE US REGULATIONS

The US regulations are mainly based on testing of actual build-up and the calculation methodologies are a result of a set of tests previously carried out. Regarding fire, the requirements are to avoid fire spreading between floors and the only way to make sure this in the case is by using similar previously tested build-ups and asking for an engineering judgment to validate the final detail. The process gets more difficult as each supplier has their tested configurations and the detail should stick with that. The test shall be carried out according to NFPA 285 and a list of ULs (Testing laboratory) tested details is available for review.

CONCLUSIONS

As shown, countries are setting their own standards in terms of façade fire safety. As a designer, international experience will help one provide safe façade detailing and material specification. We should be encouraged, therefore, to explore international regulations and see the different requirements set in other countries as this may help one find inspiration and provide an additional layer of safety when you deem it is required.