As our industry continues to evolve, harnessing and embracing new technologies and materials, our buildings morph and adapt, and our role as façade designers also changes. In the beginning, it was simple; a wall that supported the roof or floor with a hole to let in the air and light. There might be a door or a shutter to keep the rain out but very simple.

Glass is a naturally occurring substance. It is disputed whether the Egyptians or the Mesopotamians developed techniques for making glass, but it was not until the Romans started to develop new ways of making glass that glass started to be used to create windows.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Venetian artisans kept skills for glass making alive during the dark ages – in parallel with those in India and China. Techniques and chemistry of glass continued to evolve through the Middle Ages by the 1100s and 1200 and this lead to the craze for stained glass windows. This trend of stained glass windows influenced the master builders of cathedrals to develop buttresses and flying buttresses and other techniques for creating large areas of glazing.

The technology for the manufacturing of glass continued to evolve over the centuries. Over this time the crown glass technique became more prolific. As the industrial revolution matured into the Victorian age methods for producing window, glass continued to develop with glass sheets cut from large blown cylinders becoming the new mass production technique.

This technique supplied the hectares of glass used in the construction of the revolutionary Crystal Palace at the original Expo, the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in 1851.

Mass production techniques in the 1800s used timber for window frames with some use of wrought iron frames for industrial and transport buildings. In the US, larger buildings were being developed where structural steel frames carried the building’s weight in place of masonry walls.

These allowed larger areas of glazing to be created. Brick and stone were still being used to form the spandrels or solid sections of wall but no longer load bearing. This form of construction continued through the US skyscraper boom of the 1930s. With the advent of modernist architecture and the elimination of decoration and the focus on functionality, architects began to explore how glazing and façade designs could create transparency, again splitting the façade from carrying vertical building loads.

This fashion led to large areas of glazing being created with minimal framing. Initially a European style, the modernist aesthetic transferred at scaleto New York and Chicago. After the Second World War, architectural styles pulled together several new materials to develop curtain walls. In the 1950s Pilkington in the UK developed the float glass line which is still by far the most commonly used production process to this day.

Aluminium had become increasingly common in the first half of the 20th century. It was not until various alloys were developed that it became the strong and ductile material that has become common in construction. A key advantage was that aluminium could be extruded into fine and precise shapes and then tempered to give it a higher strength, making it ideal for forming window sections.

As a result, this rapidly supplanted bronze that had previously been used for high end glazing. Given the challenge of high rise construction, American manufacturers developed stick curtain wall systems. These used the third new component – widely available gaskets and seals to form complete curtain wall systems.

The next step in the evolution of curtain walling was the move from stick systems assembled on site to pre-assembled units completed in the factory. The advantages quickly became self-evident with the speed of construction using a high-quality product, made on site.

The Drive for transparency continued using new glass processing techniques on float glass. In the 1960’s, glass fins were developed and in the 1980’s, as an element in UK led high-tech architectural movement, point support glazing evolved, famously developed by renowned Irish Engineer, Arup’s Peter Rice.

And of course, we now have living façades, with green walls and vertical greenery – very dramatic and ecologically beneficial to our cities when used appropriately.

The Façade Engineer

Alongside the post-war developments in façade systems, engineering consultancies as part of their broader service might have included advice on cladding systems and some early façade engineering – example includes glazing to the Sydney Opera House.

As facade systems continued to evolve in complexity, and the role of it forming a robust future, the sealed envelope became for a while separated and less integrated with the rest of the building fabric, it became the realm solely of specialist sub-contractors. In the late eighties, engineering consultancies began to offer façade consultancy services independently, to design and advise on cladding and curtain wall systems.

We are now in 21st century and in the world of multifaceted building envelope design. Projecting the identity for the development whilst creating comfort for those inside means that the walls and windows must work very hard and in a relatively small space.

The façade zone is only a few centimeters thick, but in that space the façade should be to able to stand up, withstand the wind and any earthquakes, accommodate the building behind moving, keep water and pollution out, insulate from the heat or cold, let the warming sun and cooling breezes through, or keep the warm air and heat energy out, give views out and let the right amount of daylight in, cut noise from outside yet let people connect to birdsong and the sound of the street if desired, stop conversations and fire spreading through the building and protect us from intrusion and blasts. A tall order for walls and windows that should provide us with delight inside and out.

Due to the myriad of performance requirements and aesthetic ambitions, a broad palette of materials and systems are being used to form our façades including stone, ceramics, brick, concrete, GRC, insulation and timber which all play their part together with the gaskets, seals, adhesives, fixings and brackets to form walls and windows.

To work successfully in the field of façade design, we need to be masters of how the façade performs and its materials are used. And we also need to know how to bring these components together. Mindful of fabrication, erection, installation, financing and contractors’ and suppliers’ roles. The façade design is an intriguing and inspiring discipline where all of the skills and hard work are on display for the world to see and are tested daily by the environment.

And indeed, façades are always evolving. It is a rich area for innovation. New materials are continuously being offered to designers keen to find a new aesthetic or the next wonder material.

As a result, progress is quick and new norms are continuously being established, yet somehow the underlying systems and strategies are more constant.

The façade design needs to start early as it clearly plays a key role in the design of any building. Although having its greatest impact on the perimeter zone of a building, a well-designed façade can have a greater impact on overall ambience, and help to create a comfortable space.

This of course helps with improving energy consumption and makes a big step towards achieving green targets where energy is the biggest façade design driver now. Façades often have a large ecological impact. Embodied carbon and the impact of extraction and fabrication processes are all issues. Exploring the type of materials to be used in a façade and developing a strategy is best done at the very earliest stages of a project. Perhaps timber-framed curtain walls could be adopted as an alternative.

Only at the very start of a project, before any marks have been put down, you can ask the questions to decide what the façade should be:

• Is the building shape and orientation right for views, daylight and sun-path?

• Should the form of the façade or the building be self-shading?

• What is the right portion of windows to the solid wall?

• How to make the most of daylight?

• What should the façade be made of to reduce the ecological impact?

• How could the façade be reused or recycled at the end of its life?

These are all very fundamental questions that might drive the performance, appearance and fabric of the façade in very different directions. Even if a particular aesthetic is maintained, an early assessment of these aspects may still have a significant impact.

Evolution Of Future Of Façade Design

We have gone through some exciting years of harnessing the potential of software to imagine, design and define some spectacular building and façade forms. The façade industry is finally harnessing recent digital developments, however, for us at Arup having something quick and easy to use, that can display and record information is our aim.

To this end, we have used gaming software to develop tools that allow users to navigate around a digital twin of their façade. All sorts of design information, construction records or progress photos can be loaded onto that digital twin.

The key with this digital twin is that it needs to be easy to use for those that do not code or draw in the digital space and rather than an alternative to a BIM model, this practical way to access and interact with the information that these models contain.

Our aim is that the digital twin with all the information and records will eventually be passed on to the building owner and those who will operate and maintain the building.

We also see that the design phase will use tools that both simplify and enrich the process. By combining different skills, analysis programs and IT platforms, we are developing interactive apps that allow designers to explore design options on the fly whilst avoiding lengthy iterative loops.

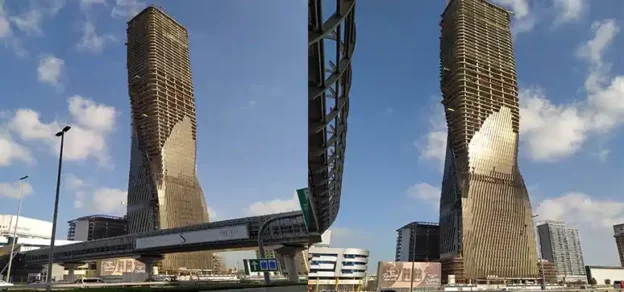

When it comes to glass, we have nearly reached the point where glass selectivity can no longer be improved, the only way to reduce energy coming in will be to reduce the amount of daylight. To avoid this and get better performance from glazing in our façades, they are becoming responsive such as the huge umbrellas that we designed for the Al Bahr towers in Abu Dhabi. Shading the building from outside only when needed.

Our Role In The Future Façades

So how will the façade designer’s role and focus change through the 21st century? The focus on environmental impact will become an ever-increasing driver. The ecological impact of the materials we choose will soon be influencing and driving our designs.

Apart from counting and measuring embodied carbon and water, and assessing pollution and other impacts, we will also plan for the future use of materials once these have served their purpose. It is inevitable that the role of the façade designer will continue to evolve and morph as more and more considerations will need to be addressed and balanced.

The key skill, though will be the ability to create an enjoyable journey from concept to handover to the operation and re-purposing of the façade for all participants. This will be enabled through embracing and harnessing new tools and applying our intellect underpinned by our collective experience in the industry.

Yet for all this focus on performance and ecological impact, we all aspire for our buildings to have an identity, to take their place in the cityscape and to bring delight to their surroundings and to the people who pass by or walk inside to work, live and play. The façade designer will orchestrate the materials, systems and geometry to realise this vision.