It was February 12, 2005, when an electrical fault on the 21st floor of the Windsor building in Madrid started a small fire. The building was unoccupied and the fire was undetected for quite some time before the city’s fire officials were notified. By the time they arrived, the magnificent 32-story structure was essentially lost. All that firefighters could do was to try for the next 18 hours to keep the fire from spreading to adjacent structures. There was no impact from a jumbo jetliner, and this fire lacked the thousands of gallons of jet fuel that so readily accelerated the World Trade Center fires. It was just a little electrical problem. So how could this fire spread so uncontrollably that it consumed eleven higher floors and turned the fourth largest structure in Spain’s capital to rubble?

Unfortunately, we may not be able to avoid such disasters where the perimeter of the structure is not effective enough to contain fires to the area of origin.

On November 21, 1980, fire ripped through the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas. 679 people were injured and 84 died in the fire. Openings in vertical shafts and seismic joints acted as chimneys, spreading smoke and heat all the way through the 26th floor. Guests found out about the fire by actually seeing smoke or because others told them. The hotel’s alarm system was destroyed before fire alarms could activate.

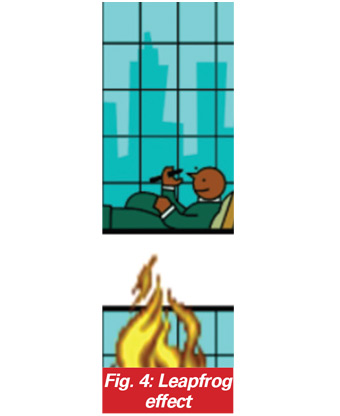

In the late evening of May 4, 1988, a fire broke out on the 9th floor of the 1st Interstate Bank Building in Los Angeles. A shrill coming from a smoke detector caused an employee to try to reset it. By then, nearly 15 minutes had passed before the blaze was reported to the fire department. By the time firefighters arrived, the fire had leapfrogged to the 13th floor and the 14th was being threatened; smoke was filing all 62 floors of the building. A maintenance employee who was investigating the source of the fire died in an elevator at the fire floor Fire officials reported that the flames had spread up inside the exterior walls, where glass fiber insulation had failed.

On October 16, 2004, the Parque Central complex in downtown Caracas, Venezuela, saw flames engulfing its 56-story office tower. What started on the 34th floor had spread over 26 floors during the 17- hour blaze. It was reported that although sprinklers were working, there was not enough water pressure to suppress the flames on the higher floors. The building was unoccupied at the time of the fire.

On December 6, 2004, fire raked the 29th floor of the LaSalle Bank Building in downtown Chicago. Fortunately, this historic 75-year old concrete and steel structure was able to contain the fire, and fire fighters on an adjacent rooftop were able to reach much of it with their hose stream. Over the six hours of the fire, the flames had only engaged the 29th and 30th floors. Just one year before, a fire on the 12th floor of the Cook County Administration Building killed six people.

On the contrary, the recent Address Hotel fire in Dubai on December 31, 2015 (New Year Eve) is a living example of an effective passive fire protection including the perimeter. The exterior burnt, but the perimeter fire barrier prevented flames, smoke and toxic gases from spreading inside the building. Hence, averting the potential disaster to human Address Hotel, Dubai Fig.2: Fire at the lives. Imagine the disaster on such a high rise had there been a

compromise on passive measures!

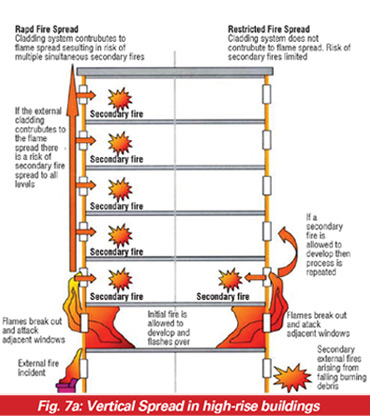

What we have learnt from these fires is that the perimeter protection needs to be the center of focus. Another aspect is that there are three ways for fire to spread from seemingly contained areas:

Poke through effect – this is where flame and hot gasses penetrate through openings in fire-rated walls and floor/ceilings to ignite combustibles on the other side.

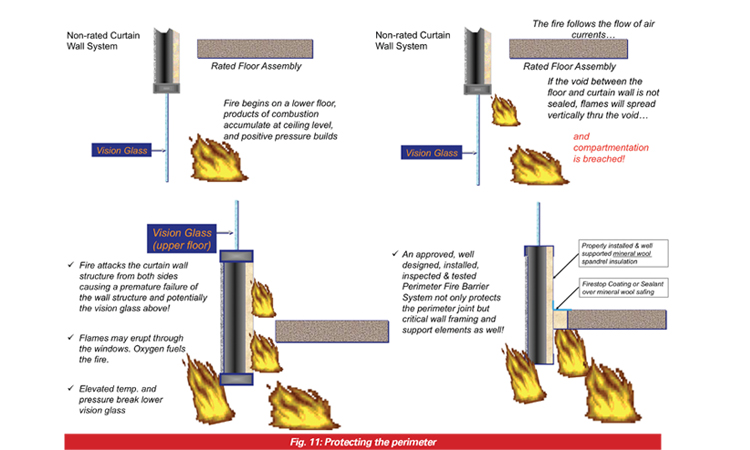

Chimney effect – is where heated surfaces create thermal zones that include upward air movement, which in turn sucks hot gasses and flames in its direction. This effect is attributed to the spread of fire upward through shafts, and also the spread of fire upward though available openings between the floor slab edge and the curtain wall (Fig. 3).

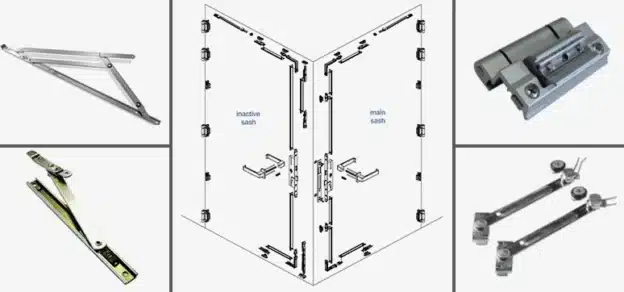

To combat these three identified ways of fire propagation, during early 70s, industry experts started designing systems to block these propagation. Many system tests came in existence including ASTM E 2307 in 1990s (Fig. 5). It is a test standard for determining the fire resistance of perimeter fire barrier systems using the intermediate multi-story test apparatus. Multistory testing has shown that spandrel height has an impact on the leapfrog effect, and can critically enhance the structure’s ability to contain a fire to the room of origin. Testing in a controlled environment, using a simulated office setting complete with office furniture, proved the point. In a system without an insulated spandrel panel between the floor slab and the curtain wall, the fire not only broke through the lower level vision glass, but spread to the floor above in just five minutes. In early 2000, both UL and OPL were testing and listing complete curtain wall systems. Today, ASTM E 2307 is the test method used by both listing agencies.

Perimeter Protection

Building Envelope

A barrier that separates the interior of the building from the outdoor (exterior) environment is termed as building envelope or exterior building facade.

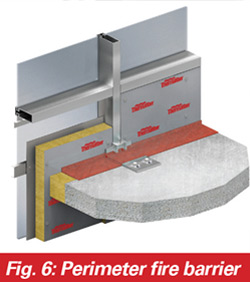

Perimeter Fire Barrier

A gap, joint, or opening, whether static or dynamic, between a fire-rated floor assembly and a non-rated exterior wall assembly. (Fig. 6)

These fires provide a glimpse of vertical fire spread (Fig. 7 a & b). Imagine, the fire enters the building and perimeter barrier is not protected!

The Problem

The architects and building owners’ desires to have unique design and aesthetics! The result is a beautiful facade without a listed and tested system. Issues with mullion and transom spacing, multiple transoms, spandrel heights, floor location with respect to the sill height, mounting brackets, etc., all vary and create a variety of conditions. Yet, in the final building approval process, perimeter fire containment must provide a system that meets the building code requirements. Complicating these requirements are some curtain wall manufacturers’ restrictions prohibiting mechanical fasters from penetrating their mullions or transoms since unitized systems use these areas for water management from the exterior of the building. The building code recognizes the need to provide supporting documentation such as tests, research reports and sufficient evidence that the proposed system meets the basic principles necessary for perimeter fire barrier protection.

The Solution

Every listed system in the Fire Resistant Directories has 5 basic principles that must be applied for a successful perimeter fire protection system:

-

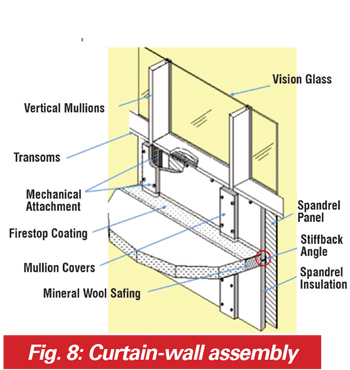

- Install a reinforcement member or a stiffener at the safe-off area behind the spandrel insulation to keep it from bowing due to the compression-fit of the safing Insulation.

- Install a reinforcement member or a stiffener at the safe-off area behind the spandrel insulation to keep it from bowing due to the compression-fit of the safing Insulation.

-

- Mechanical attachment of the Mineral Wool Spandrel Insulation –

- adhesive attachments and friction fi applications do not work. The adhesive service temperature ranges from – 30oF to 250oF. Fire exposure temperatures based on ASTM E119 very quickly exceeds the adhesive service temperatures resulting in failure of the adhesive applied attachment to hold the spandrel insulation in place (Fig. 8)

-

- Protection of the mullions with mineral wool mullion covers. Aluminium begins to melt at 1220oF. Without the mullion protection on the fire exposure side, the aluminium mullions and transoms will soften and melt. The mechanical attachments holding the mineral wool spandrel insulation in place will no longer be held in place allowing the spandrel and safing insulation to fall out resulting in a breach of flame and hot gasses to the floor above.

- Protection of the mullions with mineral wool mullion covers. Aluminium begins to melt at 1220oF. Without the mullion protection on the fire exposure side, the aluminium mullions and transoms will soften and melt. The mechanical attachments holding the mineral wool spandrel insulation in place will no longer be held in place allowing the spandrel and safing insulation to fall out resulting in a breach of flame and hot gasses to the floor above.

-

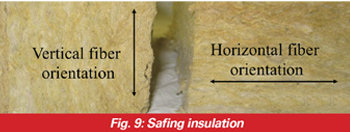

- Compression fitting and orientation of the safig insulation (Fig. 9). The safing insulation is compression fi (typically 25 per cent, but varies by system) between the slab edge and the inside face of the spandrel insulation. This compression fitting of the safing insulation creates a seal that maintains its integrity preventing flme and hot gasses from breaching through to the floor above.

- Compression fitting and orientation of the safig insulation (Fig. 9). The safing insulation is compression fi (typically 25 per cent, but varies by system) between the slab edge and the inside face of the spandrel insulation. This compression fitting of the safing insulation creates a seal that maintains its integrity preventing flme and hot gasses from breaching through to the floor above.

- Apply an approved smoke sealant material to the top of the safing insulation to provide a smoke barrier to the system (Fig. 10). The smoke seal is commonly spray applied to the top of the safing (non-fire exposure side) forming a smoke barrier with a typical L rating or leakage rating of 0. In addition, a 1” over spray as specified, onto the floor slab and spandrel insulation creates a continuous bond that adds to holding the safing material in place during the fire and building movement

Protecting the Perimeter

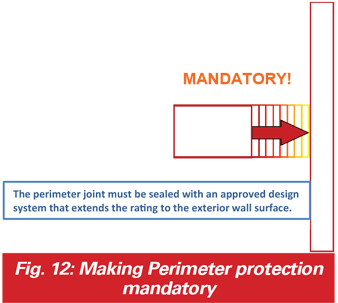

The detailed specification that guides the design, installation, inspection and maintenance – popularly termed as DIIM philosophy – is the effective solution for perimeter protection. A proven design, proper installation, mandatory inspection, periodic maintenance with effective management shall not only ensure a fire safe perimeter but also provide structural safety to the entire façade system assembly (Fig. 11, 12).

To summarize, what does an effective Perimeter Fire Barrier System do?

- Extends the rating of the floor to the wall

- Slows down the process of flame and smoke spread. Of course, it depends on window spacing and other construction factors. As well as the nature and severity of the fire

- In addition to sealing the perimeter gap, it provides structural protection and maximizes the integrity of the wall system keeping the wall and window system above intact longer

- Forces the fire to exit the building

- Protects structural elements and helps prevent catastrophic failure of the spandrel system

- Maximizes fire protection afforded by the nonrated wall

- Prevents the migration of flame, hot gases and smoke through to floors above. Smoke is the killer! 75 per cent of fire related deaths are caused by smoke

- Buys time for occupants to escape

- Buys time for fist responders to secure the building

- Provides additional protection in the event of a sprinkler or detection failure

- Provides energy savings through increased thermal efficiencies throughout the life of the building

- Immense fire and life safety benefits!

What Do Codes Say?

- All Model Codes call for the rating of the flor to extend to the exterior wall

- All Model Codes require minimum spandrel height but allow height exceptions in certain sprinklered conditions

- Extending the rated floor to the wall is madatory!

Summary

As a practicing fire consultant, a passive fire protection expert, and member of UAE Fire Code Council, I recommend that code provisions be strictly enforced globally. The DIIM Philosophy of Fire Protection is one such provision. This philosophy applies to all the fire protection and life safety systems. There may be a good design but the installation is not done properly. Third party inspection is the answer.