I have not always been a proponent of BIM, far from it. For a long time, and until a few years back, I thought that BIM was just an unnecessary complication, with limited added value as far as façade design and engineering are concerned. Without diving into it further, it seemed from the outside that BIM was simply a more complex method for documenting the façade design compared with simpler and more traditional approaches. Indeed, we had spent the better part of two decades designing façades first using hand-drawn sketches and manual computations, then subsequently using CAD applications for the production of drawings, along with finite element analysis software to speed up computations. Feeling comfortable with this state of play, I was for a while reluctant to explore alternative approaches to design documentation.

After all, this method of work had proved effective in the delivery of projects for many years and seemed to work well, with no apparent flaw or gap in the process. On the other hand, BIM seemed to me, on the face of it, to be ill-adapted to the workflow of façade design. At the time, I was under the impression that BIM was best suited for detecting clashes between architectural, structural, mechanical, and electrical components in the building, and not much else, a mere glorified 3-D CAD program.

Through a fortuitous change in circumstances, I found myself forced to dig deeper and investigate the BIM design process and its capabilities. Several years back now, DP Architects made a commitment to adopt BIM for designing and documenting all projects, and this mandate applied to all specialist companies within the group, including our engineering, landscape/arboricultural, lighting, ID, and façade teams. I would be lying if I said that the transition happened seamlessly and painlessly. Instead, it required investing time and effort in training the teams, as well as financial investment into new software and upgraded hardware solutions.

All business leaders would easily agree that once such a commitment is made, it must be in full, lest return on the investment is not realized. In for a penny, in for a pound, we decided to make the most of this shift in our internal design processes. We first ensured that the team was fully conversant with the software. Fortunately, our group has in place an in-house Academy in charge of continuous professional development, and which had developed several courses for bringing our teams up to speed with the BIM design process. For companies without such a training arm, a plethora of courses are available in many countries to help make the transition to BIM smoother.

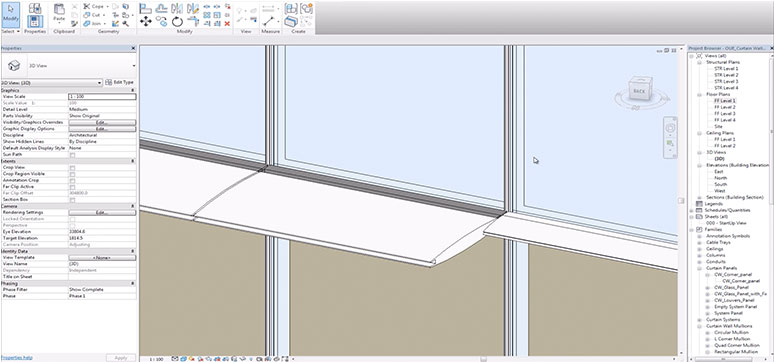

Next, we considered what would be the most appropriate method for leveraging the power of BIM in our everyday workflow. Rather than doing what we have done before using 2-D CAD but with a 3-D software this time, we set about to develop our own families of façade systems ranging from curtain walls to cladding to louvers and many more. From the outset, these families were all designed to be parametric in nature, which means that once the geometry of the façade is set in terms of floor-to-floor height and horizontal modulation, the size of the framing members, as well as the thickness of the various elements, is automatically computed and adjusted through formulas built into the definition of the families. So if changes are made at any stage in the design process the shape of the members can be tweaked on the fly, without the need to make changes to individual drawings.

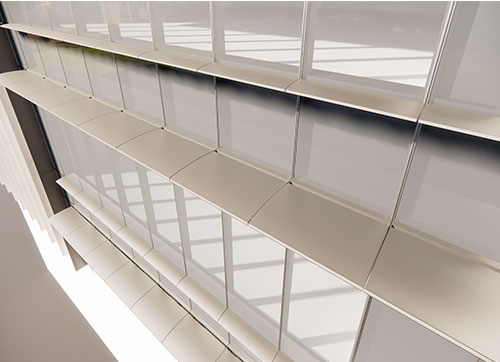

Incidentally, this approach ensures that details drawn on plans, elevations, and sections are always coordinated between each other and there is no longer a risk of mismatch. Also, the whole design process is sped up since there is no need to customize sections or systems manually for each project. Instead, the customization is built into the definition of the families. It is even possible to automate the structural analysis of the system through bilateral communication between the BIM and FEA programs. Not content with these achievements, we set about to explore all the ways to exploit the power of BIM models. One of the capabilities that we have developed is the ability to produce rapid, high-end rendering of building envelopes, along with fly-throughs and navigable models.

This allows the various parties involved in the design process including the architect, the client, and others to carefully consider the aesthetics of the façade elements, the façade systems, the material choices, the color palette, and many other parameters through visualization. To push things further, we wanted to address one of the common problems encountered in the design process of building façades. When it comes to visual mock-ups, whenever changes are required, a lot of time, effort, and money is spent in refining design elements before interested parties sign off on the design. We have thus created a parallel design stream consisting in first building an interactive virtual mock-up (iVMU in short), which can be viewed either on a computer screen, or better still using VR goggles, and which can be modified while it is being reviewed. Everything from glass color, materials, finishes, and other aspects can all be changed in real-time until everyone is satisfied with the appearance of the façade. Only then does a physical visual mock-up get built? The net result of this approach is that the approval process is cut short tremendously.

Having gone through this whole process over the past five years or so, besides extolling the virtues of BIM, I would like to share some lessons learned.

One of the interesting things that I have noticed time and time again, is that while a lot of people talk about it, not many actually understand intimately how BIM works, and how to make the best use of it. One of the most misunderstood aspects has to be the LOD (level of detail). Many articles have been written on this, and I do not need to cover the topic extensively here. Suffice to say that it is essential to set expectations right from the beginning of the project, and even better, before finalizing one’s appointment on a project. In particular, the right LOD should be done by the correct party and at the proper stage of a project. For instance, it makes little sense for the façade consultant to build the model up to LOD 100 or LOD 200, which would be tantamount to becoming the drafter for the architect. This is inefficient for both disciplines and brings no added value. Instead, once the architect has built the model up to a sufficient level of detail, then it makes sense for the façade consultant to take over and push this up to LOD 300 or greater since doing so requires a relatively deep understanding of the functioning of the façade systems.

Other than the scope of work, it is essential to develop a BIM-specific workflow. Some of the team members who felt more comfortable with other software initially preferred to start the documentation process in 2-D CAD or sometimes using SketchUp, Rhino or other programs. While it seems at first that this can result in faster progress, our experience has shown that it ultimately takes more time to convert this initial model to BIM and that we need to start from scratch when moving to BIM. This meant that BIM was considered as just an additional layer of documentation on top of the traditional ones, and thus taking more time and money to prepare. Through the development of a complete BIM workflow from start to finish, this impression was reversed.

This not only resulted in time savings, but the attitude towards BIM changed fundamentally. Instead of being viewed as something that just took more effort to produce, it was seen as a method for ensuring the quality and consistency of the project documentation.

Another important lesson learned is that to fully reap the rewards from the BIM documentation process, one needs to first invest time and effort in building a model in the correct manner, using the right processes. As a simple example, one can directly extract the façade quantities to generate a bill of quantities from the BIM model, without having to measure the façade dimensions one by one in the traditional manner. However, if the model was not built correctly, and this is particularly true for buildings with complex geometries, then quantity take-off from the model can become a real nightmare, requiring long hours to fix or amend the model.

The famous quote attributed to Greek philosopher Heraclitus “change is the only constant in life” sums it all up. Ultimately, the design of modern building envelopes, more than in the past, requires intimate collaboration between various disciplines that did not even traditionally need to work together previously, or in some cases did not even exist in the first place. On projects requiring intense inter-disciplinary coordination, the advantages of a proper BIM design process become immediately clear. Besides allowing faster and deeper coordination across various disciplines, when properly implemented, BIM opens the door to faster workflow, and simplifies or automates a number of tasks. The question seems to no longer be whether BIM will become the default method for documenting building projects, but rather when it will become the norm.