I have a confession to make: I am an inveterate science-fiction fan. I particularly enjoy reading the grand masters of the genre from the fifties to the eighties, the likes of Frank Herbert, Philip K. Dick and Isaac Asimov. What fascinates me in these books is the power of prediction of these authors. Many of the descriptions of the future in their stories have become today’s reality, only a few decades later, even though Asimov and others probably didn’t expect them to come to pass so soon. Let’s dive into a similar exercise, albeit at a much smaller scale, and take a peek at what the future likely holds for façades.

It does not take great powers of foresight to see that building envelopes of the future will need to be highly sustainable. This is a trend that has taken the construction industry by storm and is set to stay and spread. Sustainability will likely come in a number of flavours. Firstly, the materials incorporated into the façade will themselves need to be sustainable. Many materials currently used in building envelopes, such as glass, aluminium and steel, are infinitely recyclable.

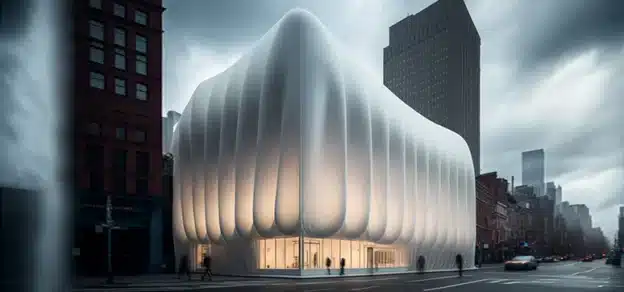

However, their production from raw materials can consume as much as 20 times more energy than producing them from recycled materials. I believe that progressively, these elements will increasingly be manufactured from recycled components, possibly even from the building envelope of demolished buildings. One of the fascinating aspects of peering into the future is that it often brings us right back to the past. After decades in oblivion, vernacular design strategies are likely to make a strong comeback, blended with modern materials and updated construction techniques.

Our forefathers had invented ways of dealing with the common issues relating to building envelopes, such as air and water infiltration, harnessing natural daylight, conserving heat, and many more. These had been refined over the centuries, to be promptly forgotten thanks to an abundance of cheap energy from fossil fuels. In times of greater respect for nature and diminishing raw materials, designers are bound to look back at these vernacular approaches to design, further enhancing and modernizing them to turn them into future building envelopes.

Over the past few years, tremendous efforts have been put into developing ever cleverer ways of using the building envelopes for energy generation from sustainable sources. While photovoltaic panels are undoubtedly the most common of these techniques, many others have also been tried or at least conceptualised, including kinetic façades leveraging wind power, bio-façades using photosynthesis to produce natural gas, etc. With the inevitable increasing scarcity of energy from fossil fuels, the use of building façade to generate energy seems inevitable. Already, solar panels for space exploration offer more than twice the efficiency of consumer panels.

With increasing demand for ever more efficient panels, research will undoubtedly come up with breakthrough photovoltaic technologies. One of the most exciting possibilities that is starting to emerge is that of transparent PV panels. Absorbing photons in the infrared range, offer the dual benefit of producing electricity while at the same time reducing the heat gain on the building. Piezoelectric façades, which generate electricity from the minute flexing of their materials from wind, do not exist now, but they could be developed in the future. Façade materials can be developed that harness the kinetic energy of raindrops impacting it.

While a single drop encapsulates a minute amount of energy, billions of drops crashing onto the building envelope could generate a significant aggregate amount of electricity. We can also imagine high-efficiency phosphorescent coatings for the façades, which would reduce or eliminate the need for street lighting. The façades would store up solar light energy during the day, and slowly release it at night. Countless other creative methods of generating energy from the building envelopes could be developed.

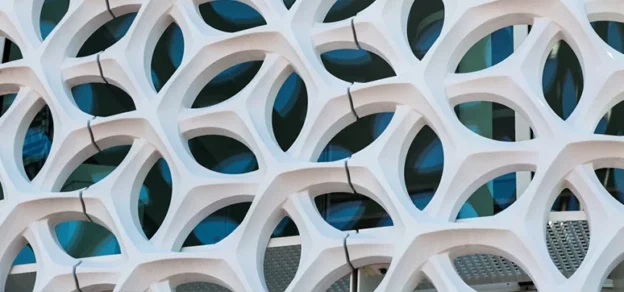

I foresee that building envelopes will increasingly become adaptive, no longer remaining static or requiring active human intervention to adapt to evolving natural conditions, as is currently the case. On overcast days, they would let more daylight in, and dim down on brighter days. Movable external shades, or blinds built into glazing have been cropping up on buildings over the past few years, but are still the exception rather than the norm. This is possibly due to higher maintenance costs, or perceived difficulties in implementation. Thermochromic, electrochromic and photochromic glazing solutions already exist today, but these are plagued either by technical performance problems or by extremely long returns on investment.

These issues are bound to be eliminated over time, allowing building envelopes to become perfectly adapted to ambient conditions, minute by minute, every day of the year. On the same topic of adaptive façades, trickle vents in façades could be linked to indoor sensors, and open automatically when CO2 or contaminants exceed certain levels within the building. Similarly, heat exchangers can be built within cladding panels, reducing the need for HVAC ducts and large AHUs. Research is even being focused on new façade materials able to clean or filter the atmosphere free of pollutants. Such technologies are only just starting to emerge, but are currently either a monopoly or prohibitively expensive, and thus limited to a few niche projects. With improving technologies and increased demand, I am convinced that they will become commonplace.

Another direction that façades are very likely to take is that of connectedness. Pretty much everything nowadays is becoming connected, and façades are unlikely to be left behind. Future façades will be controllable right from one’s smartphone, to override automatic adaptive behaviours, for instance, or to pick a colour scheme for night lighting. Information-gathering is fast becoming an obsessive activity.

Sensors built into the building envelope and linked to artificial intelligence systems will undoubtedly appear in due time. There is no limit to the information that these could yield, and more importantly how such data would be used. One exciting opportunity would be the ability to extract information on the actual performance of the façade and of the building, which could then in turn be used to optimize that performance, as well as to improve on the design of future building envelopes. While these insights into future façades are still a long shot from the ethereal but extremely high-performance force-field windows of Star Trek, I have good hope that these will come to pass within my lifetime.